By Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett

Let’s consider the health of two babies born into two different societies. Baby A is born in one of the richest countries in the world, the United States, home to more than half of the world’s billionaires. It is a country that spends somewhere between 40 and 50 percent of the world’s total spending on health care, although it contains less than 5 percent of the world’s population. Spending on drug treatments and hightech scanning equipment is particularly high. Doctors in this country earn almost twice as much as doctors elsewhere and medical care is often described as the best in the world.

Baby B is born in one of the poorer of the western democracies, Greece, where average income is not much more than half that of the United States. Whereas America spends about $6,000 per person per year on health care, Greece spends less than $3,000. This is in real terms, after taking into account the different costs of medical care. And Greece has six times fewer high-tech scanners per person than the United States.

Surely Baby B’s chances of a long and healthy life are worse than Baby A’s?

In fact, Baby A, born in the United States, has a life expectancy of 1.2 years less than Baby B, born in Greece. And Baby A has a 40 percent higher risk of dying in the first year after birth than Baby B. Had Baby B been born in Japan, the contrast would be even bigger: babies born in the United States are twice as likely to die in their first year as babies born in Japan. As in Greece, in Japan average income and average spending on health care are much lower than in the United States.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

If average levels of income don’t matter (at least in relatively rich, developed countries), and spending on high-tech health care doesn’t make so much difference, what does? We can’t say with certainty, but inequality appears to be a driving force. Greece is not as wealthy as the United States, but in terms of income, it is much more equal—so is Japan. There are now many studies of income inequality and health that compare countries, American states, or other large regions, and the majority of these studies show that more egalitarian societies tend to be healthier.1 This vast literature was given impetus by a study by one of us, on inequality and death rates, published in the British Medical Journal in 1992. In 1996, the editor of that journal, commenting on further studies confirming the link between income inequality and health, wrote:

The big idea is that what matters in determining mortality and health in a society is less the overall wealth of that society and more how evenly wealth is distributed. The more equally wealth is distributed the better the health of that society

Inequality is associated with lower life expectancy, higher rates of infant mortality, shorter height, poor self-reported health, low birth weight, AIDS, and depression. Knowing this, we wondered what else inequality might affect. To see whether a host of other problems were more common in more unequal countries, we collected internationally comparable data from dozens of rich countries on health and as many social problems as we could find reliable figures for.* The list we ended up with included:

- level of trust

- mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction)

- life expectancy and infant mortality

- obesity

- children’s educational performance

- teenage births

- homicides

- imprisonment rates

- social mobility

Occasionally, what appear to be relationships may arise spuriously or by chance. In order to be confident that our findings were sound, we also collected data for the same health and social problems—or as near as we could get to the same—for each of the 50 states of the United States. This allowed us to check whether or not problems were consistently related to inequality in these two independent settings. In short, they were— and strongly so.

To present the overall picture, we have combined all the health and social-problem data for each country, and separately for each U.S. state, to form an Index of Health and Social Problems for each country and U.S. state. Each item carries the same weight—so, for example, the score for mental health has as much influence on a society’s overall score as the homicide rate or the teenage birth rate. The result is an index showing how common all these health and social problems are in each country and each U.S. state. The higher the score on the Index of Health and Social Problems, the worse things are. (Some items, such as life expectancy, were reverse scored, so that on every measure, higher scores reflect worse outcomes.)

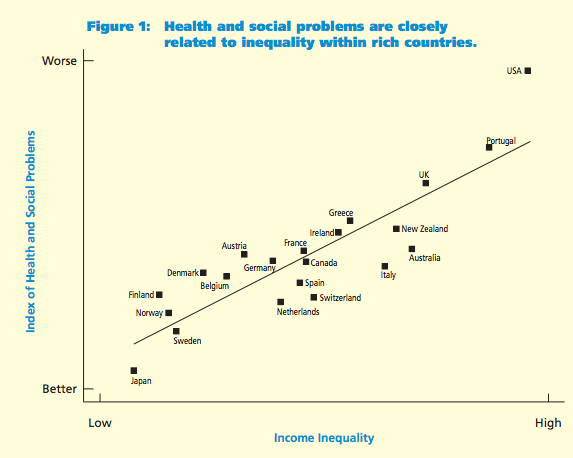

We start by showing, in Figure 1, that there is a very strong tendency for ill health and social problems to occur less frequently in the more equal countries. With increasing inequality (to the right on the horizontal axis), the score on our Index of Health and Social Problems also increases. Health and social problems are indeed more common in countries with bigger income inequalities. The two are extraordinarily closely related—chance alone would almost never produce a scatter in which countries lined up like this.

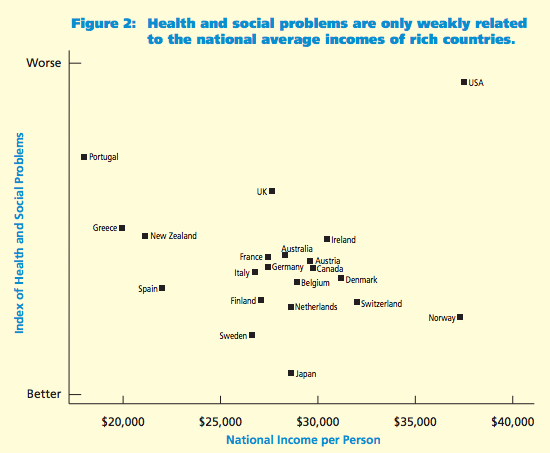

To emphasize that the prevalence of poor health and social problems in rich countries really is related to inequality rather than to average living standards, we show in Figure 2 the same Index of Health and Social Problems, but this time in relation to average incomes (national income per person). It shows that there is no clear trend toward better outcomes in richer countries.

The evidence from the United States confirms the international picture. Across states, health and social problems are related to income inequality, but not to average income levels.

It is remarkable that these measures of health and social problems in the two different settings tell so much the same story. The problems in rich countries are not caused by the society not being rich enough (or even being too rich), but by the material differences between people within each society being too big. What matters is where we stand in relation to others in our own society.

Inequality, not surprisingly, is a powerful social divider, perhaps because we all tend to use differences in living standards as markers of status differences. We tend to choose our friends from among our near equals and have little to do with those much richer or much poorer. Our position in the social hierarchy affects who we see as part of the ingroup and part of the out-group—us and them—thus affecting our ability to identify and empathize with other people.

The importance of community, social cohesion, and solidarity to human well-being has been demonstrated repeatedly in research showing how beneficial friendship and involvement in community life are to health. Equality comes into the picture as a precondition for getting the other two right. Not only do large inequalities produce problems associated with social differences and the divisive class prejudices that go with them, but they also weaken community life, reduce trust, and increase violence.

It may seem obvious that problems associated with relative deprivation should be more common in more unequal societies. However, if you ask people why greater equality reduces these problems, the most common assumption is that greater equality helps those at the bottom. The truth is that the vast majority of the population is harmed by greater inequality.

Across whole populations, rates of mental illness are three times as high in the most unequal societies compared with the least unequal societies. Similarly, in more unequal societies, people are almost ten times as likely to be imprisoned and two or three times as likely to be clinically obese, and murder rates may be many times higher. The reason why these differences are so big is, quite simply, because the effects of inequality are not confined just to the least well-off: instead, they affect the vast majority of the population. For example, as epidemiologist Michael Marmot frequently points out, if you took away all the health problems of the poor, most of the problem of health inequalities would still be untouched. For a more detailed example, let’s take a look at the relationship between inequality and literacy.

Across whole populations, rates of mental illness are three times as high in the most unequal societies compared with the least unequal societies. Similarly, in more unequal societies, people are almost ten times as likely to be imprisoned and two or three times as likely to be clinically obese, and murder rates may be many times higher. The reason why these differences are so big is, quite simply, because the effects of inequality are not confined just to the least well-off: instead, they affect the vast majority of the population. For example, as epidemiologist Michael Marmot frequently points out, if you took away all the health problems of the poor, most of the problem of health inequalities would still be untouched. For a more detailed example, let’s take a look at the relationship between inequality and literacy.

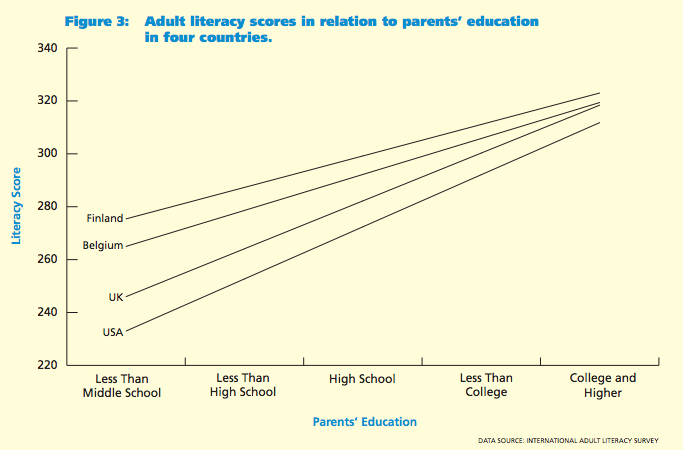

It is often assumed that the desire to raise national standards of performance in fields such as education is quite separate from the desire to reduce educational inequalities within a society. But the truth may be almost the opposite of this. It looks as if the achievement of higher national standards of educational performance may actually depend on reducing the social gradient in educational achievement in each country. Douglas Willms, professor of education at the University of New Brunswick in Canada, has provided striking illustrations of this. In Figure 3 (below), we show the relation between adult literacy scores from the International Adult Literacy Survey and their parents’ level of education—in Finland, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

This figure suggests that even if your parents are well educated—and so, presumably, of high social status—the country you live in makes some difference to your educational success. But for those lower down the social scale with less well-educated parents, it makes a much larger difference. An important point to note, looking at these four countries, is the steepness of the social gradient—steepest in the United States and the United Kingdom, where inequality is high; flatter in Finland and Belgium, which are more equal. It is also clear that an important influence on the average literacy scores in each of these countries is the steepness of the social gradient. The United States and the United Kingdom have low average scores, pulled down across the social gradient. In contrast, Finland and Belgium have high average scores, pulled up across the social gradient.

Willms has demonstrated that the pattern shown in Figure 3 holds more widely—internationally among 12 developed countries, as well as among Canadian provinces and U.S. states. The tendency toward divergence also holds; Willms consistently finds larger differences at the bottom of the social gradient than at the top.

Willms has demonstrated that the pattern shown in Figure 3 holds more widely—internationally among 12 developed countries, as well as among Canadian provinces and U.S. states. The tendency toward divergence also holds; Willms consistently finds larger differences at the bottom of the social gradient than at the top.

What is most exciting about our research is that it shows that reducing inequality would increase the well-being and quality of life for all of us. Far from being inevitable and unstoppable, the deterioration in social well-being and the quality of social relations in society is reversible. Understanding the effects of inequality means that we suddenly have a policy handle on the well-being of whole societies.

Politics was once seen as a way of improving people’s social and emotional well-being by changing their economic circumstances. But over the last few decades, the bigger picture seems to have been lost, at least in the United States, the United Kingdom, and several other rich countries in which inequality has increased dramatically. People are now more likely to see psychosocial well-being as dependent on what can be done at the individual level, using cognitive behavioral therapy—one person at a time—or on providing support in early childhood, or on the reassertion of religious or family values. Every problem is seen as needing its own solution—unrelated to others. People are encouraged to exercise, not to have unprotected sex, to say no to drugs, to try to relax, to sort out their work-life balance, and to give their children “quality” time. The only thing that many of these policies do have in common is that they often seem to be based on the belief that the poor need to be taught to be more sensible. The glaringly obvious fact that these problems have common roots in inequality and relative deprivation disappears from view. However, it is now clear that income distribution provides policymakers with a way of improving the psychosocial well-being of whole populations. Politicians have an opportunity to do genuine good.

Rather than suggesting a particular route or set of policies to narrow income differences, it is probably better to point out that there are many different ways of reaching the same destination. Although the more equal countries often get their greater equality through redistributive taxes and benefits and through a large welfare state, countries like Japan manage to achieve low levels of inequality before taxes and benefits. Japanese differences in gross earnings (before taxes and benefits) are smaller, so there is less need for large-scale redistribution.

What matters is the level of inequality you finish up with, not how you get it. However, in the data there is also a clear warning for those who want low public expenditure and taxation: if you fail to avoid high inequality, you will need more prisons and more police. You will have to deal with higher rates of mental illness, drug abuse, and every other kind of problem. If keeping taxes and benefits down leads to wider income differences, the ensuing social ills may force you to raise public expenditure to cope.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

There may be a choice between using public expenditure to keep inequality low, or to cope with social harm where inequality is high. An example of this balance shifting in the wrong direction can be seen in the United States during the period since 1980, when income inequality increased particularly rapidly. During that period, public expenditure on prisons increased six times as fast as public expenditure on higher education, and a number of states have now reached a point where they are spending as much public money on prisons as on higher education.

Not only would it be preferable to live in societies where money can be spent on education rather than on prisons, but policies to support families—such as providing high-quality, publicly funded preschool—would have meant that many of those in prison would have been working and paying taxes instead of being a burden on public funds.

Modern societies will depend increasingly on being creative, adaptable, inventive, well-informed, and flexible, able to respond generously to each other and to needs wherever they arise. Those are characteristics not of societies in hock to the rich, in which people are driven by status insecurities, but of populations used to working together and respecting each other as equals.

This article is excerpted, from The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, published in 2009 by Bloomsbury Press.

2017 January 26

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!