October 24, 2021

Excerpt from Ours: The Case for Universal Property by Peter Barnes

Capitalism as we know it has two egregious flaws: it relentlessly widens inequality and destroys nature. Its ‘invisible hand,’ which is supposed to transform individual self-seeking into widely shared well-being, too often doesn’t, and governments can’t keep up with the consequences. For billions of people around the world, the challenge of our era is to repair or replace capitalism before its cumulative harms become irreparable.

Among those who would repair capitalism, policy ideas abound. Typically, they involve more government regulations, taxes and spending. Few, if any, would fundamentally alter the dynamics of markets themselves. Among those who would replace capitalism, many would nationalize a good deal of private property and expand government’s role in regulating the rest.

This book explores the terrain midway between repairing and replacing capitalism. It envisions a transformed market economy in which private property and businesses are complemented by universal property and fiduciary trusts whose beneficiaries are future generations and all living persons equally.

Economists wrangle over monetary, fiscal and regulatory policies but pay little attention to property rights. Their models all assume that property rights remain just as they are forever. But this needn’t and shouldn’t be the case. My premise is that capitalism’s most grievous flaws are, at root, problems of property rights and must be addressed at that level.

.

Property rights in modern economies are grants by governments of permission to use, lease, sell or bequeath specific assets — and just as importantly, to exclude others from doing those things. The assets involved can be tangible, like land and machinery, or intangible, like shares of stock or songs.

Taken as a whole, property rights are akin to gravity: they curve economic space-time. Their tugs and repulsions are everywhere, and nothing can avoid them. And just as water flows inexorably toward the ocean, so money, goods and power flow inexorably toward property rights. Governments can no more staunch these flows than King Canute could halt the tides.

That said, the most oft-forgotten fact about property rights is that they do not exist in nature; they are constructs of human minds and societies. The assets to which they apply may exist in nature, but the rights of humans to do things with them, or prevent others from doing them, do not. Their design and allocation are entirely up to us.

In this book, I take our existing fabric of property rights as both a given and merely the latest iteration in an evolutionary process that has been and will continue to be altered by living humans. Future iterations of the fabric will therefore be a product not only of the past, but also of our imagination and political will in the future. And, while eliminating existing property rights is difficult, adding new ones is less so.

Before we talk about universal property, we need to look at co-inherited wealth, for that is what universal property is based on.

A full inventory of co-inherited wealth would fill pages. Consider, for starters, air, water, topsoil, sunlight, fire, photosynthesis, seeds, electricity, minerals, fuels, cultivable plants, domesticable animals, law, sports, religion, calendars, recipes, mathematics, jazz, libraries and the internet. Without these and many more, our lives would be incalculably poorer.

Universal property does not involve all of all those wonderful things. Rather, it focuses on a subset: the large, complex natural and social systems that support market economies, yet are excluded from representation in them. This subset includes natural ecosystems like the Earth’s atmosphere and watersheds, and collective human constructs such as our legal, monetary and communications systems. All these systems are enormously valuable, in some cases priceless. Not only do our daily lives depend on them; they add prodigious value to markets, enabling corporations and private fortunes to grow to gargantuan sizes. Yet the systems were not built by anyone living today; they are all gifts we inherit together. So it is fair to ask, who are their beneficial owners?

There are, essentially, three possibilities: no one, government, or all of us together equally. This book is about what happens if we choose the third option, and create property rights to apply it.

Let’s start with an obvious question: how much is this subset of co-inherited wealth worth? While it is impossible to put a precise number on this, estimates have been made. In 2000, the late Nobel economist Herbert Simon stated, “If we are very generous with ourselves, we might claim that we ‘earned’ as much as one fifth of [our present wealth]. The rest [eighty percent] is patrimony associated with being a member of an enormously productive social system, which has accumulated a vast store of physical capital and an even larger store of intellectual capital.”

Simon arrived at his estimate by comparing incomes in highly developed economies with those in earlier stages of development. The huge differences are due not to the rates of economic activity today — indeed, young economies often grow faster than mature ones — but to the much larger differences in institutions and know-how accumulated over decades. A few years later, World Bank economists William Easterly and Ross Levine confirmed Simon’s math. They conducted a detailed study of rich and poor countries and asked what made them different. They found that it wasn’t natural resources or the latest technologies. Rather, it was their social assets: the rule of law, property rights, a well-organized banking system, economic transparency, and a lack of corruption. All these collective assets played a far greater role than anything else.

The preceding analysis doesn’t include ecosystems gifted to us by nature, but Robert Costanza and a worldwide team of scientists and economists took a crack that in 1997. They found that natural ecosystems generate a global flow of benefits — including fresh water supply, soil formation, nutrient cycling, waste treatment, pollination, raw materials and climate regulation — worth between $25 trillion and $87 trillion a year. That compares with a gross world product of about $80 trillion.

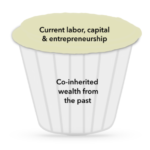

These calculations are precise enough to suggest that we are greatly confused about where our wealth today comes from. We think it comes from the fevered efforts of today’s businesses and workers, but in fact they merely add icing to a cake that was baked long ago.

WHERE TODAY’S WEALTH COMES FROM

The calculations also suggest that we should devote far more attention to co-inherited wealth than we currently do. Nowadays, economics textbooks don’t even mention such wealth, much less its magnitude. Nor do Wall Street analysts or financial reporters. This is a grievous oversight that greatly impedes our understanding of our economy. It is like trying to comprehend the universe without taking dark matter into account, or analyzing a business while ignoring over eighty percent of its assets.

Paying more attention to co-inherited wealth, however, is just a first step. If we want to change market outcomes, we need to functionally connect this wealth to real-time economic activity. And to do that, we need property rights, managers and beneficial owners.

What is it?

Universal property, as I use the term in this book, is a set of non-transferable rights backed by a subset of wealth we inherit together. Such property isn’t mine, yours or the state’s, but ours — literally held in trust for all of us, living and yet-to-be born. It belongs to us not because we earned it but because we co-inherited it, as if from common ancestors. This co-inheritance is, or should be, a universal economic right, just as voting is a universal political right.

To say that all of us are co-inheritors of universal property does not, however, mean that we should manage it ourselves. That job should be assigned to two types of institutions: trusts with a fiduciary responsibility to future generations, and pension-like funds that pay equal dividends to all living persons within their jurisdictions. An example of the latter is the Alaska Permanent Fund, which has paid equal dividends to every Alaskan since 1980. Examples of the former include large land trusts, such as the National Trust, a conserver of land and historic buildings in the UK, and thousands of local trusts whose missions include land conservation, affordable housing, education and community development.

An archetypal, albeit theoretical, example of universal property is the ‘sky trust’ I proposed in my 2001 book, Who Owns The Sky? It is archetypal because it includes features of pension-like funds and fiduciary trusts simultaneously. In it, a fiduciary trust is charged with protecting the integrity of the atmosphere (or one nation’s share of it) for future generations. It auctions a declining quantity of permits to dump carbon into our sky, and divides the proceeds equally. A version of this model was introduced in Congress in 2009 by Representative (now Senator) Chris van Hollen of Maryland and re-introduced several times since.

A bit of history may be useful here. For millennia, humans lived in tribes in which almost all property was communal. Individual land ownership emerged at the beginning of the Holocene when our ancestors became settled agriculturalists. Rulers granted ownership of land to heads of families, usually males. Often, military conquerors distributed land to their lieutenants. Titles could then be passed to heirs — typically, oldest sons got everything, a practice known as primogeniture. In Europe, Roman law codified these practices.

The Roman Institutes of Justinian distinguished three kinds of property:

• res privatae, private property owned by individuals, including land and personal items;

• res publicae, public property owned by the state, such as public buildings, aqueducts and roads; and

• res communes, common property, including air, water and shorelines.

The Institutes also identified a category called res nullius, or‘nobody’s things,’ that included uninhabited land and wild animals. Such things weren’t immune to propertization; they just hadn’t been propertized yet. Uninhabited land could be privatized by occupying it, wild animals by capturing them. A bird in hand was property; a bird in the bush was not.

In England during the Middle Ages, most of the valuable land was privately owned by barons, the Church and the Crown, but sizable common areas were also set aside for villagers. These commons were essential for the villagers’ sustenance: they provided food, water, firewood, building materials and medicines.

There were many battles over what should be private and common. Until 1215, English kings granted exclusive fishing rights to their lieges; then, the Magna Carta established fisheries and forests as res communes. However, starting in the seventeenth century and continuing into the nineteenth, in a process known as enclosure, local gentry fenced off village commons and converted them to private holdings. Impoverished peasants then drifted to cities and became industrial workers. Landlords invested their agricultural profits in manufacturing, and modern times, economically speaking, began.

Universal property lies somewhere between individual and state property. In Roman terms, it converts a large swath of res nullius into a version of res communes: instead of being owned by nobody, many gifts of nature and society would be owned beneficially by all.

While we are thinking historically, it is worth remembering that the limited liability corporation, which is so dominant today, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Prior to the nineteenth century, there were barely a handful of corporations in the UK and US; the dominant form of business organization was the partnership (in which all partners are liable for the partnership’s debts). Limited liability corporations arose only when it became necessary to amass capital from strangers.

Similarly, until the eighteenth century, there was no such thing as intellectual property. Ideas and inventions floated freely in the air. The world’s first copyright law, the Statute of Anne, was passed in England in 1710. Today, the world is flooded with copyrights, patents, trademarks and trade secrets, all essential to the profits of giant corporations.

Like intellectual property, universal property can turn intangible assets into rights respected by markets and capable of generating income. And like corporations that manage assets on behalf of shareholders, trusts can manage assets on behalf of future generations and all of us equally. The reason there is more intellectual than universal property today is that capital owners have fought for their most beneficial forms of property rights, while we, the people, have not. But that could change if we set our minds to it.

The idea of universal property isn’t new. It was the invention of Thomas Paine, the English-born essayist who inspired America’s revolution and much else. Indeed, virtually all the ideas in this book can be traced back to a single essay he wrote in the winter of 1795/96.

Paine led an extraordinary life. Unlike other American Founders, he wasn’t born to privilege. The son of a Quaker corset-maker, he emigrated to Philadelphia in 1774 and found himself in the thick of pre-revolutionary ferment. Inspired, he wrote a pamphlet called Common Sense, which quickly sold half a million copies (in a nation of three million) and transformed the prevailing discontent with King George III into ardour for independence and a united democratic republic.

And that was just the beginning. Another series of essays, The American Crisis, kept the patriotic flame alive as the war for independence slogged. After America’s victory, Paine returned to England to raise money for an iron bridge he wanted to build over the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. While there, he wrote Rights of Man in response to Edmund Burke’s repudiation of the French Revolution. Charged with sedition, he escaped to France, where he was greeted as a hero and elected to the National Assembly. Then came the Jacobin Terror, during which he was sentenced to death for having opposed the execution of Louis XVI. He spent ten months in Luxembourg Prison before being saved by the American ambassador, James Monroe, who persuaded his captors that Paine was a citizen of the United States, France’s ally, not Britain, its foe.

It was during his years in France that Paine wrote his last great essay, Agrarian Justice. In Rights of Man, Paine had criticized the English Poor Laws and argued for what today would be called a welfare state, including universal education, pensions for the elderly and employment for the urban poor, all paid for by taxes. In Agrarian Justice he went farther, arguing that poverty should be systemically eliminated with universal income from jointly inherited property.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

There are two kinds of property, he wrote: “firstly, property that comes to us from the Creator of the universe — such as the Earth, air and water; and secondly, artificial or acquired property — the invention of men.” Because humans have different talents and luck, the latter kind of property must necessarily be distributed unequally, but the first kind belongs to everyone equally. It is the “legitimate birthright” of every man and woman.

To Paine, this was more than an abstract idea; it was something that could be implemented within a laissez faire economy. But how? How could the Earth, air and water possibly be distributed equally to everyone? Paine’s practical answer was that, though the assets themselves can’t be distributed equally, income derived from them can be.

How again? Here Paine came up with an ingenious solution. He proposed a ‘national fund’ to pay every man and woman about $18,000 (in today’s dollars) at age twenty-one, and $12,000 a year after age fifty-five. In effect, nature’s gifts would be transformed into grants and annuities that would give every young person a start in life and every older person a dignified retirement. Revenue would come from ‘ground rent’ paid by private land owners upon their deaths. Paine used contemporary French and English data to show that a ten percent inheritance tax — his mechanism for collecting ground rent — could fully pay for the universal grants and annuities.

An important nuance here is that the rent would be collected not only on a deceased person’s land, but on his entire estate. It would thereby recoup many of society’s gifts as well as nature’s. And in Paine’s view, there was nothing wrong with this. “Separate an individual from society, and give him an island or a continent to possess, and he cannot…be rich. All accumulation therefore of personal property, beyond a man’s own hands produce, is derived to him by living in society; and he owes, on every principle of justice, of gratitude, and of civilization, a part of that accumulation back again to society from whence the whole came.” What Paine invented here, in my retrospective opinion, was a prescient stroke of genius. Long before Wall Street sliced collateralized debt obligations into risk-based tranches, Paine designed a simple way to monetize co-inherited wealth for the equal benefit of everyone. It is a model as relevant — and revolutionary — today as it was then.

Excerpt from Ours: The Case for Universal Property by Peter Barnes

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!