Editor’s Note: In an effort to center New Economic Thinking in the discussion of the COVID-19 crisis, we’ve curated a list of Evonomics articles relevant to this moment—including this one. Check out the full list here.

29 December 2015

Chicago’s nineteenth ward reeked of overripe fruit and kerosene the day Mary Stastch killed her baby. According to the Chicago Tribune on July 29, 1911 the unemployed single mother and recent immigrant from Austria left Cook County Hospital earlier that week and “wandered about Chicago for two days with the baby in her arms, looking for work.” But with the growing labor crisis leaving nearly 250,000 people jobless her search would have been difficult even without a newborn in tow.

As if that wasn’t enough, the following day more than three hundred police descended on the largely immigrant neighborhood around Maxwell Street in what was described as “a day of rioting and wild disorder such has not been seen in Chicago since the garment workers’ strike” the previous year. Wagons were overturned, grocery store windows smashed, and fruit carts doused with fuel in a desperate struggle between peddlers, police, and strike breakers. In the eery silence that followed Mary Stastch quietly strangled her infant. Cradling the limp child in her arms she then carried the body several miles to where it was later discovered, hidden behind a residence on Carroll Avenue.

“Cases of maternal infanticide are gripping,” explains feminist scholar Rebecca Hyman, “because they seem to violate an inherent natural law.” A mother’s affection for her child is thought to be absolute, a fact of evolution in which women have been “endowed with a nurturing maternal instinct.”

Yet, throughout history, from the fictional Medea to the tragic reports of modern times, women have taken the lives of their children under a variety of contexts, whether it is to punish the father, escape from the burden of motherhood, or even to protect a child from what they perceive as a fate worse than death. In this regard humans share yet another feature, albeit a tragic one, with nonhuman animals since females in a variety of species have been observed to abandon, abuse, or even kill their own offspring. To stress the importance of motherhood in human societies today, how can we best understand this behavior so that we can better predict, and prevent, its recurrence?

Get Evonomics in your inbox

One hundred years after Mary Stastch took her child’s life another Chicago immigrant may have some answers. Dario Maestripieri has spent most of his career studying maternal behavior in primates. In particular, he’s focused on the factors that influence a mother’s motivation towards her young. As a professor of Comparative Human Development, Evolutionary Biology, Neurobiology, and Psychiatry at the University of Chicago he has enjoyed the kind of cross-disciplinary success that most scientists only dream of. His 153 academic papers and six books have been cited more than a thousand times by scholars (including this one) in many of the world’s top scientific journals. In a paper published in the June, 2011 edition of the American Journal of Primatology Maestripieri lays out the argument he’s built over the last two decades. What he shows is that one of the most serious impacts on maternal behavior, one with potentially lethal results, is so common in modern life as to be nearly invisible: stress.

Of course, contrary to the advice of most doctors, stress is actually a good thing and is particularly adaptive during motherhood. Whenever animals experience a stressful situation, whether that involves chasing down a gazelle, escaping from a hawk, or asking a cute guy out on a date, our adrenal gland releases massive amounts of the hormone cortisol into our blood stream. Cortisol, in turn, increases the production of glucose and aids in metabolizing fats, proteins, and carbohydrates for even more blood sugar. Within moments we have enough energy on hand to attack or flee depending on the circumstances. Stress therefore serves as an adaptive response to prepare the body for adversity.

Both during pregnancy and after parturition cortisol increases significantly for new and experienced mothers alike. This suggests, to no one’s great surprise, that motherhood is an especially stressful time in a female primate’s life. Dario Maestripieri has previously shown that this response is directly related to protective behaviors that keep a mother’s infant from harm. For example, in one study, rhesus macaque mothers who exhibited high levels of anxiety (such as repeated self-scratching, a behavior associated with high cortisol levels) while they were observing their infant near a dangerous group member, were much more likely to immediately intervene and retrieve them.

“Maternal anxiety,” explains Maestripieri, “can significantly increase the chances of offspring survival and the reproductive success of the parent.” Natural selection has provided mothers with an early warning system, one that can alert them to danger before others are even aware of the risk.

However, as the maxim goes, there can be too much of a good thing. In addition to increasing the body’s available energy, cortisol also serves to inhibit other systems, such as digestion or immune function, that can be spared over the short term. The reason why, as Stanford neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky quipped in his book Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, should be relatively straightforward:

“You have better things to do than digest breakfast when you are trying to avoid being someone’s lunch.”

But periods of long term or excessive stress can cause serious physiological damage and an increased susceptibility to disease. It can also result in what Maestripieri calls the “dysregulation of emotion,” or turning what would be an otherwise adaptive response into a potentially dangerous overreaction.

“A large body of evidence,” Maestripieri says, “indicates that extremely high or chronically elevated cortisol levels due to stress can impair maternal motivation and result in maladaptive parenting behavior.”

Maestripieri has conducted numerous studies demonstrating the connection between high levels of stress and maladaptive parenting. For example, his research has shown that, among pigtail macaques, maternal abuse of infants is frequently precipitated by socially stressful events. Likewise, he’s found that abusive rhesus macaque mothers have neurochemical profiles similar to those of humans with posttraumatic stress disorder.

“Specifically,” Maestripieri says, “it has been shown in humans that stress is a major risk factor for postpartum depression and for child neglect and abuse.” But his recent findings are the most revealing yet about how stress and motherhood can interact in ways that are frighteningly relevant for today’s society.

While its appearance suggests an idyllic utopia of crystal blue waters, palm trees, and white sandy beaches, the island of Cayo Santiago is actually a breeding ground for class warfare. For more than seventy years this Caribbean island has been home to a provisioned colony of rhesus macaques, one that offers the ideal conditions to study the effects of stress and group dynamics.

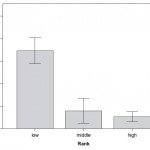

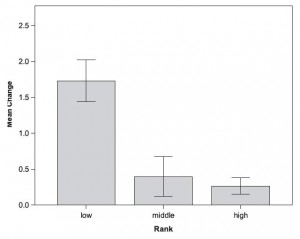

Average Change in Cortisol Levels For Pregnant/Lactating Females in Three Social Ranks. Reproduced From Hoffman et al. (2010).

Over a period of two years Maestripieri and his doctoral student Christy Hoffman studied the cortisol responses among 70 females, all of whom were experienced mothers. Blood samples were regularly collected from each individual and behavioral data were recorded to determine the dominance hierarchy among the mothers. The study confirmed earlier results showing heightened reactions to stress for all mothers from conception through the end of weaning. However, the largest change in cortisol levels occurred among the lowest ranking females and was four times greater than those who were higher in the pecking order. The most likely explanation for this, say the scientists, was a lack of control.

“Low-ranking mothers may perceive their infants to be at risk from other group members to a greater extent than middle- and high-ranking females,” says Hoffman. However, unlike the higher ranking females, these low status mothers “experience greater constraints in their ability to provide protection for offspring.”

Supporting this interpretation, the team analyzed the colony’s mortality records covering a period of ten years and found that infants born to low-ranking females were much more likely to die in their first year than those born to high-ranking ones. As a result, low-ranking mothers were living in a state of constant panic. Resources were harder to come by and there was danger at every turn, for themselves but especially for their offspring. Unable to control the social forces around them their innate warning system screamed at high alert and their anxiety simply grew, expanding out of proportion as a result of the social inequality. This created an environment with a clear link to abuse, neglect, and even infanticide.

But are such findings applicable for our species? After all, humans have the ability to make conscious choices and design political systems that protect the least among us. Haven’t we improved on the harsh conditions faced by our distant monkey cousins? The answer to this couldn’t be more clear: humans are very different from macaques. We’re much worse. The anxiety caused by human inequality is unlike anything observed in the natural world. In order to emphasize this point, Robert Sapolsky put all kidding aside and was uncharacteristically grim when describing the affects of human poverty on the incidence of stress-related disease.

“When humans invented poverty,” Sapolsky wrote, “they came up with a way of subjugating the low-ranking like nothing ever before seen in the primate world.”

This is clearly documented in studies looking at human inequality and the rates of maternal infanticide. The World Health Organization Report on Violence and Health reported a strong association between global inequality and child abuse, with the largest incidence in communities with “high levels of unemployment and concentrated poverty.” Another international study published by the American Journal of Psychiatry analyzed infanticide data from 17 countries and found an unmistakable “pattern of powerlessness, poverty, and alienation in the lives of the women studied.”

The United States currently leads the developed world with the highest maternal infanticide rate (an average of 8 deaths for every 100,000 live births, more than twice the rate of Canada). In a systematic analysis of maternal infanticide in the U.S., DeAnn Gauthier and colleagues at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette concluded that this dubious honor falls on us because “extreme poverty amid extreme wealth is conducive to stress-related violence.” Consequently, the highest levels of maternal infanticide were found, not in the poorest states, but in those with the greatest disparity between wealth and poverty (such as Colorado, Oklahoma, and New York with rates 3 to 5 times the national average). According to these researchers, inequality is literally killing our kids.

Did the stress associated with inequality also play a role in the death of Mary Stastch’s child? We can’t ever know what this young woman was thinking or feeling at the time but, according to Michelle Oberman who documented Mary’s story, it would have been an important factor.

“She would have been desperately in need of food, clothing, shelter, and money,” says Oberman. “Indeed, it was all but inevitable that harm would befall that child.”

While the ultimate explanation for Mary Stastch’s murder must remain stubbornly obscure from us, the conditions that give rise to her modern counterparts around the world are starting to become more clear. Even though macaques shared a common ancestor with humans more than 25 million years ago, they may have something very important to teach us about the world we live in today.

As social mammals, primates are powerfully affected by their standing in a given society. Even a bond that is as integral as that between a mother and her child can be severed if social conditions are pitted against her. If we’re serious about stressing motherhood in our society it will take more than simply reaching out to at-risk populations. It will require addressing the root cause of societal ills and preventing those risks before they start.

References

Friedman, S. (2005). Child Murder by Mothers: A Critical Analysis of the Current State of Knowledge and a Research Agenda, American Journal of Psychiatry 162 (9), 1578-1587. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1578

Gauthier, D., Chaudoir, N., & Forsyth, C. (2003). A Sociological Analysis of Maternal Infanticide in the United States, 1984-1996, Deviant Behavior 24 (4), 393-404. DOI: 10.1080/713840226

Hoffman, C., Ayala, J., Mas-Rivera, A., & Maestripieri, D. (2010). Effects of reproductive condition and dominance rank on cortisol responsiveness to stress in free-ranging female rhesus macaques,American Journal of Primatology 72 (7), 559-565. DOI: 10.1002/ajp.20793

Maestripieri, D. (2011). Emotions, stress, and maternal motivation in primates, American Journal of Primatology 73 (6), 516-529. DOI: 10.1002/ajp.20882

Oberman, M. (2002). Understanding Infanticide in Context: Mothers Who Kill, 1870-1930 and Today, The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 92 (3/4), 707-738. DOI: 10.2307/1144241

Sapolsky, R. (1998). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!