We are now far enough through the cycle of Piketty analysis to know how it will end. There will be no clear victor. Those who were instinctively supportive of Piketty’s thesis before reading his book will be able to ignore any alleged flaws in his data, and challenges to either his mathematical theory of capital accumulation or his narrative theory of capital destruction. This group will conclude what they already knew – inequality is too high and rising and should be addressed with higher taxation. On the other side, those who were immediately skeptical of his thesis will dwell on the discrepancies in his data and the challenges to his mathematics and history. This group will conclude that his thesis can safely be dismissed.

Of the small minority who have the time and patience to delve into multiple layers of argument and counter argument there will be a vanishingly small proportion who are persuaded to materially alter their position, based on what they have learned. A much larger number of people, on both sides, will find reason to consider their prior point of view as vindicated by the Piketty debate. This group will emerge from the affair with more deeply entrenched positions than before. As a result the economic debate will become more polarised and even more dysfunctional. In short, the confusion generated by Piketty’s book will push an already deeply dysfunctional economics further into crisis.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

Perversely the deepening crisis in economics is a triumph for Thomas Kuhn and his theory of scientific revolutions.

Anyone familiar with the science fiction of Isaac Asimov will know what is meant by a Seldon Crisis. According to Asimov’s stories, Hari Seldon was the supreme exponent of ‘psychohistory’ a fictitious mathematical branch social science (which bears more than a passing resemblance to mainstream economics) which allowed Hari Seldon to forecast social crises and revolutions with precision, hundreds of years into the future. In a sense Thomas Kuhn is the Hari Seldon of scientific theory. In Kuhn’s famous book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions , he maps out in detail, how scientific crises begin, how they mature and how they are eventually resolved. Kuhn even spells out how the old guard will lash out against any new ideas in a final futile attempt to defend their own discredited theories.

It is fascinating to look at the debate over Thomas Piketty’s work through the lens of Thomas Kuhn’s analysis. Just as Kuhn predicted, new data is unable to resolve disputes once a field has entered a state of pre-revolutionary crisis. On one side Piketty has provided enough evidence to persuade the pre-converted and on the other side Chris Giles, of the Financial Times, has now provided enough doubt to persuade the un-converted. According to Kuhn, this crisis phase will persist indefinitely, regardless of the emergence of new data, until a new way to think about economic theory emerges – this will be the paradigm shift which resolves the crisis. The various competing schools of thought will see in any new data what they want to see. They will use their individual interpretations to convince themselves that they and their theories are correct and their opponents are wrong. Confirmatory data will be embraced uncritically while any inconvenient challenging data will be doubted, ignored, discarded or belittled.

In the debate over Piketty’s data this process of selective interpretation has been common on both sides. Those on the left-wing embraced Piketty’s data uncritically but immediately rejected the analysis of the Financial Times. Those on the right-wing largely ignored Piketty’s data until the Financial Times provided them with an excuse to belittle it. As Kuhn forecast, Piketty’s data has served only to harden rather than change opinions.

Similarly, when it came to either Piketty’s mathematical model of capital accumulation or his narrative model of capital destruction, the response was largely driven by prior opinions. For anyone whose priors were confirmed, Piketty’s models were accepted without challenge. On the other hand, those whose priors were challenged went looking for reasons to doubt Piketty’s arguments. I fell into this latter camp. I instinctively disagreed with at least two aspects of Piketty’s argument. Firstly my experience as a professional investor meant that ‘I knew’ he was wrong to assert that the return on capital was both structurally high, at around 5%, and largely independent of the rate of economic growth – his famous r > g relationship. This feeling sent me on a quest to challenge his r > g inequality which lead to the following arguments: The Magical Mathematics of Mr Piketty Part I and Part II and Credit in the 21st century.

In addition, coming from a coal mining community in the North East of England ‘I knew’ that it was the union movement, not World War I, that achieved greater equality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This prompted me to examine his ideas about capital destruction in World War I. And this examination in turn furnished me with another reason to doubt Piketty’s historical analysis: The Horrible History of Mr Piketty.

Naturally constructing these arguments has left me, as Kuhn predicted, more firmly convinced that I was correct to be sceptical of Piketty’s thesis. On the other hand a few people have read my rebuttals of Piketty and a written their own counter rebuttals. Doubtless this exercise has left them also more certain of their own opposite views!

For those of us who enjoy debating macroeconomic issues this is all good entertainment. However, as a process for deciding how best to manage our economies, this sterile, divisive, debate is a dreadful way to proceed. Economics is ultimately responsible for setting the policies which determine the livelihoods of millions of people – we therefore owe it to ourselves and our children to find a better way to conduct the debate.

Fortunately Thomas Kuhn did more than just describe what scientific crises looks like, he also told us what needs to be done to resolve a scientific crisis. Kuhn explained we need to find a way to reconcile the apparently irreconcilable world views of the various competing schools of thought.

On the face of it appears an almost impossible task to find a theory which is able to agree with both the instinctively pro-Piketty crowd with his instinctive opponents. But with a little imagination there may be a way through this impasse.

Let’s step back from the details of Piketty’s data and his models, for a moment, and consider just the essence of Piketty’s thesis: capitalism has an inbuilt tendency to cause wealth polarization which must be counteracted with progressive taxation.

Now let’s consider the antithesis to Piketty’s argument: inequality must be preserved as it is the driving force of competition, innovation, economic progress and ultimately wealth generation.

According to Kuhn the path to progress is in finding a way to reconcile these competing world views. In other words, we need the paradigm shift which makes it clear why inequality and redistribution are both necessary features of a healthy economic system.

The problem is not as difficult as it looks:

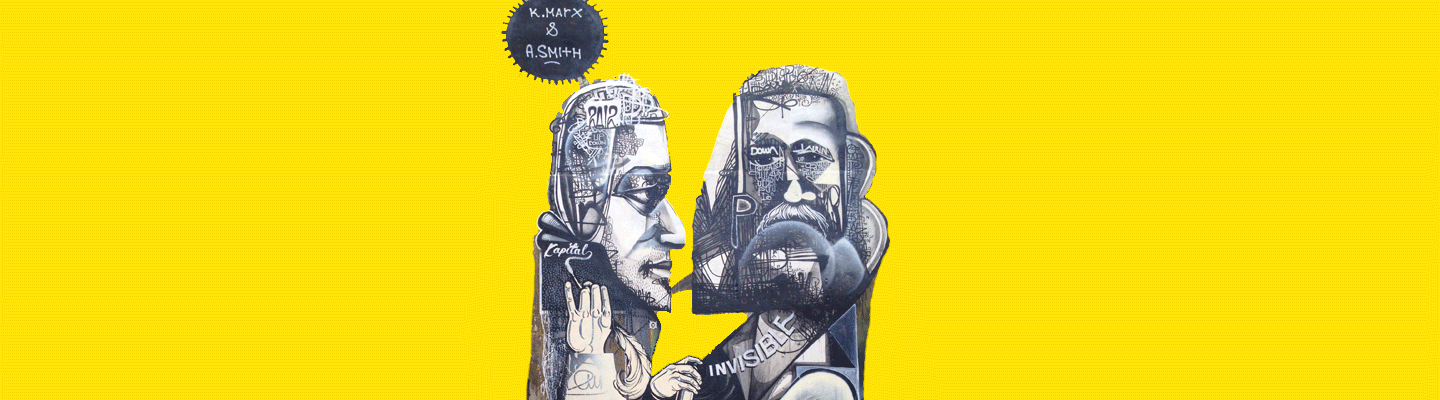

Step 1: Accept that Adam Smith was correct

As a first step let’s side with those on the right-wing and agree that Adam Smith’s thesis is correct: it is the pursuit of self-interest that is the key motivating force for economic activity, innovation and progress. I doubt that many readers will have difficulty with this step.

Step 2: Accept that Charles Darwin was correct

Now let’s add just a small corollary to Smith’s idea. Let’s imagine that what really motivates us is not the pursuit of absolute wealth but rather the pursuit of relative wealth. Put differently we are not neoclassical optimizers but rather Darwinian competitors – we are motivated by our relative position in the social pyramid. (For those interested I provide some reasons to support this notion in Money, Blood and Revolution)

Step 3: Recognise the darker side of Darwinian competition

Our Darwinian competitive spirit has both a bright side and a dark side. On the bright side the spirit of competition spurs us on to achieve more than our peers. This is what continues to motivate us to generate ever more economic progress even when we have long since satiated our immediate needs. However, on the dark side, it also means that our social position is paramount. It is our wealth and status relative to our peers that dominate our behaviour. Those on the bottom of the social pyramid are motivated to compete to move up to a higher position. But for those at the top of the social pyramid, with few above them, the overriding priority becomes an urge to preserve the status quo, to ensure that those beneath them do not move up to displace them.

Darwinian competition motivates those at the bottom to strive for improvement while it motivates those at the top to strive for preservation of the status quo. For this reason an unfettered, Darwinian, competitive economy tends to evolve into a near stagnant feudal system.

Step 4: Accept that Karl Marx was also correct

Now let’s accept that the Karl Marx and therefore the essence of Piketty’s argument is also correct: capitalism does indeed have an inbuilt tendency toward wealth polarization.

Despite my previous posts criticising aspects of Piketty’s thesis I believe these wealth polarizing forces are real. I just happen to think Piketty has homed in on the wrong mechanisms.

Piketty has chosen to focus on the return on capital and its relationship to the rate of economic growth. By contrast I believe he could have built a more robust theoretical argument for wealth polarisation based on the cost of credit rather than the return on capital.

Those at the bottom of the social pyramid are, almost by definition, less credit-worthy than those at the top of the social pyramid. For this reason those at the bottom must pay higher interest rates to borrow money, reflecting their greater default risk. The ultra-rich can borrow almost directly from the central bank at rates often close to or below zero percent, in real terms. By contrast, the ultra-poor are forced into the hands of payday lenders charging hundreds or even thousands of percent in interest.

This differential cost of credit runs throughout the social pyramid. As most lending occurs vertically through the pyramid, with the poor borrowing from the rich, through the banking sector, these differential interest rates ensure a steady trickle-up effect, whereby wealth flows from poor to rich.

Differential interest rates also cause a secondary wealth polarising mechanism. As the profitability of any business venture is a function of the gap between the cost of capital and return on capital, it follows that any given venture will be more profitable, and less risky, to those who can borrow money at the lowest possible rates. For this reason there are more potentially viable business ventures available to the rich than to the poor – as the saying goes: ‘the first million is always the hardest’.

Step 5: Properly integrate the state sector into our economic models

Having acknowledged the validity of Marx’s critique of capitalism and the darker side of our Darwinian nature the next step, toward a sensible unified economic paradigm, is to recognise that we have already established the necessary institutional arrangements to deal with both our Darwinian instincts and capitalism’s wealth polarization.

Marx failed to recognise that, at least in Britain, America and France, the social revolutions he called for in had already happened. The English Glorious Revolution followed by the American and French Revolutions began the democratising reforms necessary to check the power of those at the top of the social pyramid and, eventually, to counterbalance to the trickle up effect of capitalism.

Democracy eventually brought improvements in workers’ rights, minimum wages, state funded education, social security and of course redistributive taxation. All of which helped gradually establish the conditions necessary to allow those lower down the social order to compete more effectively with those above them.

In short, the partnership of democracy and capitalism established a circulatory flow of wealth through the economy – capitalism pushed wealth up the social pyramid and democracy pushed it back down. Together this partnership of capitalism and democracy placed the whole of society onto an invigorating competitive treadmill, enabling those at the bottom of the pyramid to compete and also obliging those at the top to compete.

It is forgivable that Marx failed to recognise that his revolution was already in progress as he wrote his ‘Capital’. Indeed it could be argued that his writings helped complete those revolutions. On the other hand I have rather less sympathy for the stance taken in Piketty’s ‘Capital’ where, like Marx before him, he chooses to analyse capitalism as an isolated entity, largely ignoring the role of the state sector with its progressive taxation and transfer payments. For example, his r > g relationship fails to take into account that, when thinking of wealth accumulation, we should consider returns net of taxation.

In Marx’s ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’ he calls for a number of reforms. Two of the most important – “A heavy progressive or graduated income tax” and “Free education for all children in public schools” – have already been implemented. We should not now resurrect a new version of Marx’s critique of capitalism without acknowledging that these countervailing redistributive arrangements are already in place. A more reasonable approach would be to recognise their presence and to debate their size and construction.

[Intriguingly for those who are now arguing for monetary reform the Communist Manifesto also calls for: “Centralisation of credit in the hands of the State, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.” The parallels with the recently published ideas of the Positive Money organisation are interesting.]

Thinking about our economic system with a circulatory flow model is far from a complete model of an economy. It may better be thought of as the kernel of a new approach to economic thinking – the first step in rethinking economics. Nevertheless, with only a little thought it becomes possible to see how such a circulatory growth model could reconcile the key ideas of Smith, Marx, Keynes, Hayek, Minsky, Schumpeter, Fisher, Veblen and Darwin with the ideas of the institutional, historical and behavioural schools of economics.

I discuss these ideas in greater detail in Money, Blood and Revolution where I also explain how the circulatory growth model can be used to understand why the excessive use of monetary stimulus – both through low rates and quantitative easing – leads directly to: structurally low economic growth, higher social inequality, deflationary pressures, high government deficits and an inevitable pressure for higher taxation.

It is impossible to know if this circulatory growth idea represents a ‘correct’ model of the economy, but at least until a better idea comes along, it could provide a useful conceptual device to encourage a more constructive debate over both macroeconomic theory and policy.

There is an unfortunate corollary to Kuhn’s analysis. Kuhn also explained the difficulty of changing people’s opinions once formed. Kuhn notes that the leaders of a discipline almost never accept the new ideas necessary to resolve the crisis in their field. Instead they simply insist that the way forward is for everyone to agree with them. Therefore the old guard either refuse to engage with the new ideas or attacks both them and their proponents. So far the reaction to the circulatory growth idea proposed in Money, Blood and Revolution has been precisely as Kuhn would have anticipated. Paul Krugman, for example, has managed to finesse the fine line of both rejecting the idea and refusing to acknowledge it! See: Paradigming is hard.

My reply to Krugman is simple: if you have got better ideas on how to fix the dismal failure of economic theory then let’s hear them. If you do not have the ideas then at least have the courtesy to respect those of us who are making an honest attempt to find a way out of the current confusion. With thousands of students of economics around the world now engaged in an open revolt against the teachings of mainstream economics the position that ‘all is well in economic theory’ is no longer tenable.

2015 september 4

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!