By Steve Roth

The standard definition of income makes much of rich people’s income invisible.

If your home or stock-portfolio value goes up over a decade or three, have you received “income,” “saved,” or increased your “savings”? It sure as heck feels like it. It increases your asset holdings and net worth. It’s new money in your pocket that you can spend now and in your retirement. (Maybe you have to sell things or borrow against them. Whatever.) How is that not income?

But in economics — actually right down to the core of national accounting methods — capital gains aren’t counted as income. And they don’t contribute to “saving.” Those gains are completely invisible to a huge bulk of the economics work (both empirical and theoretical) that is built on income and saving concepts and measures.

Even Piketty and company, who importantly include capital gains income in their income data, don’t include it in their theorizing about income and saving. Ditto most Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) work, despite (or because of?) that group’s rigorous accounting-based approach.

There’s a historical reason: When FDR tasked Simon Kuznets and his cohorts to create the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) in the 1930s, they had no means to measure or estimate people’s assets, net worth, “wealth.” (The NIPAs didn’t have balance sheets, and still don’t. Cap gains don’t, can’t, exist in the NIPAs.) So they built incomplete accounting constructs that they called “Income” and “Saving,” that they could estimate based on measurable flows within the accounting period.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

Those incomplete constructs shamble on today in the Fed’s Flow of Funds matrix. It’s a closed-loop accounting construct that’s only closed because it balances to an artificial and incomplete balancing item called “Saving” (based on the incomplete definition of income). The Flow of Funds don’t sum to change in net worth — the very “balance” in “balance sheets.” Because cap gains are missing.*

Theory: The justification is that income is payments to “factors of production” — labor, capital, natural resources, etc. But think about it: when existing-asset markets go up, that’s the market looking at our previously created assets and “realizing” they’re worth more than they thought they were at the time of production and sale. So cap gains are delivering income from production — production in previous periods.

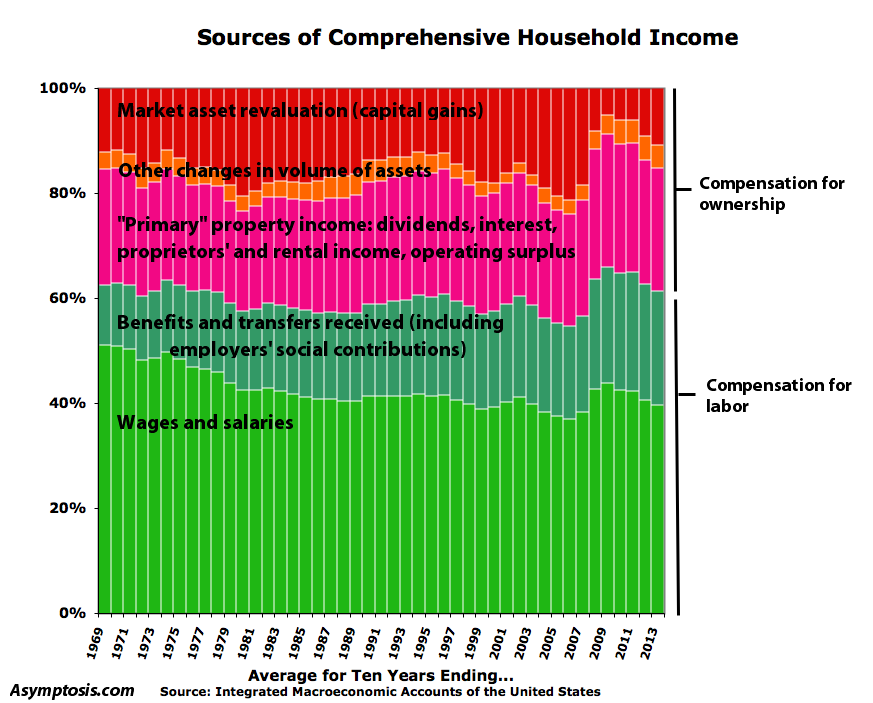

Data: Capital gains comprise 15-25% of comprehensive household income (it varies a lot year to year).

Distribution estimates vary, but some are eye-popping: as much as 96% of capital gains income may go to those making more than a million dollars a year.

In 2011, the top 1% of U. S. earners (median income, $1.4 million) got 36% of their income from capital gains — all invisible in the standard measure of “income.” This is only realized capital gains, of course, and it ignores capital gains from the $20-trillion+ of invisible assets held in offshore tax havens.

Politics: by rendering capital gains income largely invisible to accounting, these incomplete income and saving measures make those flows largely invisible to economists, and hence to politicians, and to the whole political conversation about equality and distribution.

It’s darned hard to understand how income and saving work in economies if you’re ignoring 15–25% of households’ income and saving.

It’s not hard to guess which group benefits from that incomplete discussion.

* For accounting dweebs: The Flow of Funds Matrix (pages 1 and 2 of the Fed’s quarterly Z.1 report) ignores the Revaluation and Other Changes in Volume accounts, which you’ll find in the Z.1’s Table S.3.a, and in the Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts of the United States (the IMAs) — both based on the modern international System of National Accounts (SNAs). For an explanation of this comprehensive, mark-to-market, capital-gains-inclusive income accounting, see Haig-Simons accounting. See also discussions of Haig-Simons in Godley and Lavoie’s Monetary Economics.

2016 January 25

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!