Editor’s Note: In an effort to center New Economic Thinking in the discussion of the COVID-19 crisis, we’ve curated a list of Evonomics articles relevant to this moment—including this one. Check out the full list here.

2017 February 12

Almost two centuries ago an idea was born with such explanatory power that it created shock waves across all of human society and whose aftershocks we’re still feeling to this day. It’s so simple and yet so powerful, that after all these years, it remains capable of making people question their very faith.

The idea of which I speak is that through random mutation and natural selection, every living thing around us was created through millions and even billions of years of what is effectively trial and error, not designed by some intelligent creator. It is the process of evolution through natural selection.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

It’s almost impossible for many people to accept that everything around us, including our own lives, could ever be the result of trial and error, but that’s what the scientific method has revealed. Mutations happen. Some of them work better than others depending on the environment. A longer beak here and a longer neck there can be the difference between life and death. Successful mutations are passed on. Iterations continue generation after generation. Discovering this process of evolution was one of the great accomplishments of our species. It’s also possibly the most powerful reason to support another world-changing idea — an unconditional basic income.

Let me explain.

Markets as Environments

Our economy is a complex adaptive system. Much like how nature works, markets work. No one central planner is deciding what natural resources to mine, what to make with them, how much to make, where to ship everything to, who to give it to, etc. These decisions are the result of a massively decentralized widely distributed system called “the market,” and it’s all made possible with a tool we call “money” being exchanged between those who want something (demand) and those who provide that something (supply).

Money is more than a decentralized tool of calculation however. It’s also like energy. It powers the entire process like the eating of food powers our own bodies and the sun powers plants. Without food, we starve, and without money, markets starve. A sufficient amount of money for all market participants is absolutely key to the market system for it to work properly.

If you’ve ever played Monopoly this should be apparent. The game would not work if all players started the game with nothing. Some wouldn’t even make it once around the board. Additionally, if no one received $200 for then passing Go, the game would end a lot sooner. Ultimately the game always grinds to a halt once everyone but one person is all out of money, which is inevitable. No money, no purchases, no market, no game. Game over.

Supply and Demand as Trial and Error

With sufficient money however, markets adapt and evolve based on trial and error. Someone thinks of something to create or do. If people like it, it does well. If people don’t like it, it goes away. What does well is modified. If people like the modified version, it does well. If they don’t, it goes away. If they like it enough, the original version goes away. Survival of the fittest we call it. This is the evolution of goods and services, which runs on supply and demand, which both in turn run on money and one other thing — the willingness to take risks.

Risks as Genetic Mutation

Taking risks is equivalent to random genetic mutation in this biological analogy. A new product or service introduced into the market can result in success or failure. The outcome is entirely unknown until it’s tried. What succeeds can make someone rich and what fails can bankrupt someone. That’s a big risk. We traditionally like to think of these risk-takers as a special kind of person, but really they’re mostly just those who are economically secure enough to feel failure isn’t scarier than the potential for success.

As a prime example, Elon Musk is one of today’s most well-known and highly successful risk takers. Back in his college years he challenged himself to live on $1 a day for a month. Why did he do that? He figured that if he could successfully survive with very little money, he could survive any failure. With that knowledge gained, the risk of failure in his mind was reduced enough to not prevent him from risking everything to succeed.

This isn’t just anecdotal evidence either. Studies have shown that the very existence of food stamps — just knowing they are there as an option in case of failure — increases rates of entrepreneurship. A study of a reform to the French unemployment insurance system that allowed workers to remain eligible for benefits if they started a business found that the reform resulted in more entrepreneurs starting their own businesses. In Canada, a reform was made to their maternity leave policy, where new mothers were guaranteed a job after a year of leave. A study of the results of this policy change showed a 35% increase in entrepreneurship due to women basically asking themselves, “What have I got to lose? If I fail, I’m guaranteed my paycheck back anyway.”

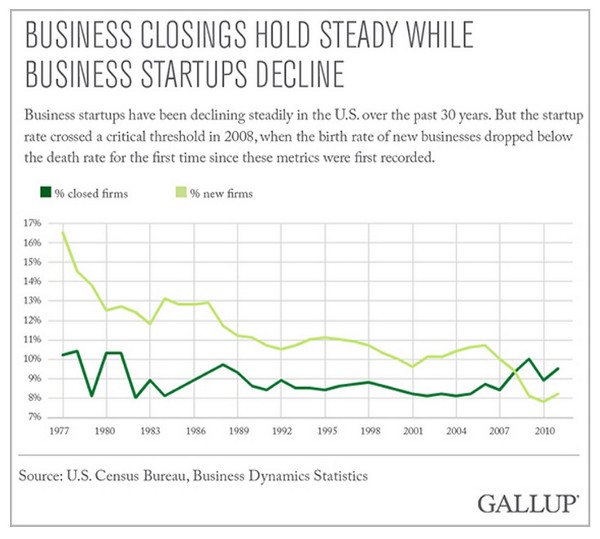

Meanwhile, entrepreneurship is currently on a downward trend. Businesses that were less than five years old used to comprise half of all businesses three decades ago. Now they comprise about one-third. Businesses are also closing their doors faster than new businesses are opening them. Until recently, this had never previously been true here in the US for as long as such data had been recorded. Startup rates are falling. Why? Risk aversion due to rising insecurity.

Meanwhile, entrepreneurship is currently on a downward trend. Businesses that were less than five years old used to comprise half of all businesses three decades ago. Now they comprise about one-third. Businesses are also closing their doors faster than new businesses are opening them. Until recently, this had never previously been true here in the US for as long as such data had been recorded. Startup rates are falling. Why? Risk aversion due to rising insecurity.

Growing Insecurity

For decades now our economy has been going through some very significant changes thanks to advancements in technology, and we have simultaneously been actively eroding the institutions that pooled risk like trade unions and our public safety net. Incomes adjusted for inflation have not budged for decades, and the jobs providing those incomes have gone from secure careers to insecure jobs, part-time and contract work, and now recently even gig labor in the sharing economy.

Decreasing economic security means a population decreasingly likely to take risks. Looking at it this way, of course startups have been on the decline. How can you take the leap of faith required for a startup when you’re more and more worried about just being able to pay the rent?

None of this should be surprising. The entire insurance industry exists to reduce risk. When someone is able to insure something, they are more willing to take risks. Would there be as many restaurants if there was no insurance in case of fire? Of course not. The corporation itself exists to reduce personal risk. Entrepreneurship and risk are inextricably linked.Reducing risk aversion is paramount to innovation.

Failure as Evolution

So the question becomes, how do we reduce the risks of failure so that more people take more risks? Better yet, how do we increase the rate of failure? It may sound counter-intuitive, but failure is not something to avoid. It’s only through failure that we learn what doesn’t work and what might work instead. This is basically the scientific method in a nutshell. It’s designed to rule out what isn’t true, not to determine what is true. There is a very important difference between the two.

This is also how evolution works, through failure after failure. Nature isn’t determining the winner. Nature is simply determining all the losers, and those who don’t lose, win the game of evolution by default. So, the higher the rate of mutation, the more mutations can fail or not fail, and therefore the quicker an organism can adapt to a changing environment. In the same way, the higher the rate of failure in a market economy, the quicker the economy can evolve.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

There’s also something else very important to understand about failure and success. One success can outweigh 100,000 failures. Venture capitalist Paul Graham of Y Combinator has described this as Black Swan Farming. When it comes to truly transformative ideas, they aren’t obviously great ideas, or else they’d already be more than just an idea, and when it comes to taking a risk on investing in a startup, the question is not so much if it will succeed, but if it will succeed BIG. What’s so interesting is that the biggest ideas tend to be seen as the least likely to succeed.

Now translate that to people themselves. What if the people most likely to massively change the world for the better, the Einsteins so to speak — the Black Swans, are oftentimes those least likely to be seen as deserving social investment? In that case, the smart approach would be to cast an extremely large net of social investment, in full recognition that even at such great cost, the ROI from the innovation of the Black Swans would far surpass the cost.

This happens to be exactly what Buckminster Fuller was thinking when he said, “We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest.” That is a fact, and it then begs the question, “How do we make sure we invest in every single one of those people such that all of society maximizes its collective ROI?”

What if our insistence on making people earn their living is preventing those one in ten thousand from making incredible achievements that would benefit all the rest of us in ways we can’t even imagine? What if our fears of each other being fully free to pursue whatever most interests us, including nothing, is an obstacle to an explosion of entrepreneurship and truly huge innovations the likes of which have never been seen?

Fear as Death

What it all comes down to is fear. FDR was absolutely right when he said the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Fear prevents risk-taking, which prevents failure, which prevents innovation. If the great fears are of hunger and homelessness, and they prevent many people from taking risks who would otherwise take risks, then the answer is to simply take hunger and homelessness off the table. Don’t just hope some people are unafraid enough. Eliminate what people fear so they are no longer afraid.

If everyone received as an absolute minimum, a sufficient amount of money each month to cover their basic needs for that month no matter what — an unconditional basic income — then the fear of hunger and homelessness is eliminated. It’s gone. And with it, the risks of failure considered too steep to take a chance on something.

If everyone received as an absolute minimum, a sufficient amount of money each month to cover their basic needs for that month no matter what — an unconditional basic income — then the fear of hunger and homelessness is eliminated. It’s gone. And with it, the risks of failure considered too steep to take a chance on something.

But the effects of basic income don’t stop with a reduction of risk. Basic income is also basic capital. It enables more people to actually afford to create a new product or service instead of just think about it, and even better, it enables people to be the consumers who purchase those new products and services, and in so doing decide what succeeds and what fails through an even more widely distributed and further decentralized free market system.

Such market effects have even been observed in universal basic income experiments in Namibia and India where local markets flourished thanks to a tripling of entrepreneurs and the enabling of everyone to be a consumer with a minimum amount of buying power.

Basic income would even help power the sharing economy. For example, imagine how much an unconditional monthly income would enable people within the Open Source Software (OSS) and free software movements (FSM) to do the unpaid work that is essentially the foundation of the internet itself.

Markets as Democracies

Markets work best when everyone can vote with their dollars, and have enough dollars to vote for products and services. The iPhone exists today not simply because Steve Jobs had the resources to make it into reality. The iPhone exists to this day because millions of people have voted on it with their dollars. Had they not had those dollars, we would not have the iPhone, or really anything else for that matter. Voting matters. Dollars matter.

Evolution teaches us that failure is important in order to reveal what doesn’t fail through the unfathomably powerful process of trial and error. We should apply this to the way we self-organize our societies and leverage the potential for universal basic income to dramatically reduce the fear of failure, and in so doing, increase the amount of risks taken to accelerate innovation to new heights.

Failure is not an option. Failure is the goal. And fear of failure is the enemy.

It’s time we evolve.

Originally published at Scott Santen’s Medium blog here.

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!