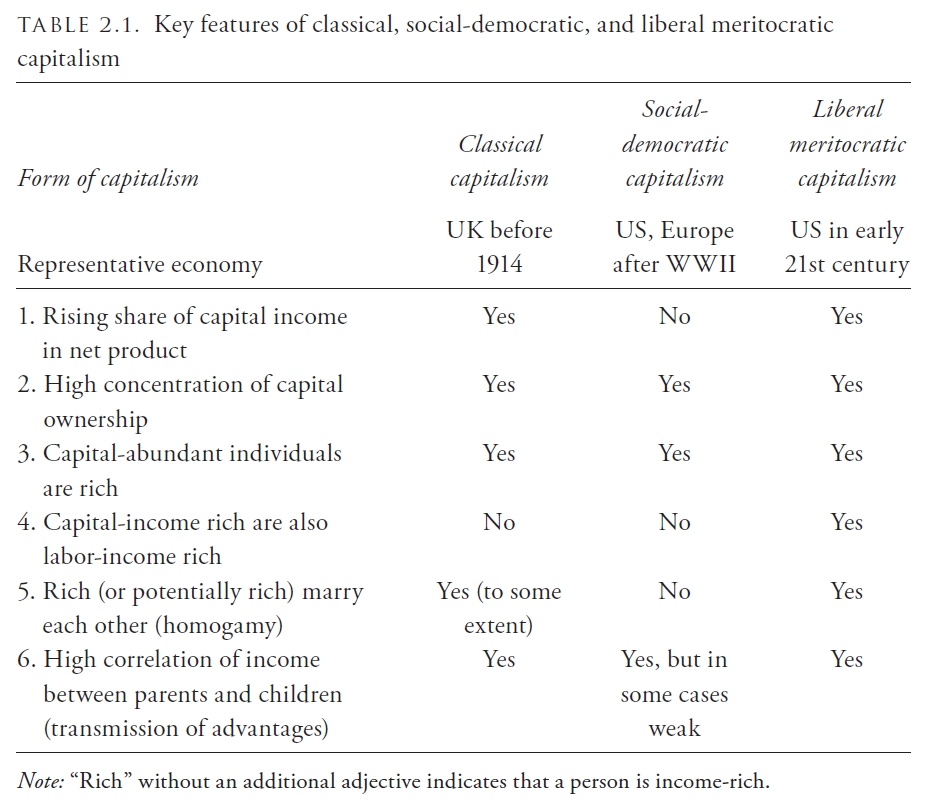

Liberal meritocratic capitalism can be best understood by contrasting its distinguishing features with those of nineteenth-century classical capitalism and with social-democratic capitalism, as it existed between approximately the end of the World War II and the early 1980s in Western Europe and North America. We are dealing here with “ideal-typical” features of the systems and ignoring details that varied among countries and across time. But in the following sections, where I focus on liberal meritocratic capitalism alone, I discuss these features in detail for a country that can be taken as prototypical, namely the United States.

Table 2.1 summarizes the differences between the three historical types of capitalism through which Western economies have passed. For simplicity, I take the United Kingdom before 1914 as representative of classical capitalism, Western Europe and the United States from the end of World War II through the early 1980s as representative of social-democratic capitalism, and the twenty-first- century United States as representative of liberal meritocratic capitalism. Note that because the two key features that differentiate liberal from meritocratic capitalism, taxation of inheritance and broadly available public education, have weakened in the United States over the past thirty years, the country may have shifted toward a model of capitalism that is more “meritocratic” and less “liberal.” However, since I am using the United States as an example of all rich capitalist countries, I think it is still acceptable to speak of liberal meritocratic capitalism as a single model.

We start with the key characteristic of every capitalist system—the division of net income between the two factors of production: owners of capital (owners of property more generally) and workers. This division need not coincide with two distinct classes of individuals. It will do so only when one class of individuals receives income only from capital, and a different class receives income only from labor. As we shall see, whether or not these classes overlap is what distinguishes different types of capitalism.

Data on the division of total net income between capital and labor is murky for the period before 1914, since the first estimates for the United Kingdom, which were made by the economist Arthur Bowley, were not done until 1920. Based on this work, it has been argued that the income shares of capital and labor are more or less constant—a trend that came to be called Bowley’s Law. Data produced by Thomas Piketty (2014, 200– 201) for the United Kingdom and France have cast severe doubt on that conclusion, even for the past. For the United Kingdom in the period 1770– 2010, Piketty found that the share of capital oscillated between 20 and 40 percent of national income. In France, between 1820 and 2010, it varied even more widely: from less than 15 percent in the 1940s to more than 45 percent in the 1860s. The percentages became more stable after World War II, however, reinforcing belief in Bowley’s Law. Paul Samuelson, for example, in his influential Economics, included Bowley’s Law among the six basic trends of economic development in advanced countries (although he did allow for some “edging upward of labor’s share”) (Samuelson 1976, 740). However, since the late twentieth century, the share of capital income in total income has been rising. While this tendency has been quite strong in the United States, it has also been documented in most developed countries, as well as developing countries, although the data for the latter must be taken with a strong dose of caution (Karabarbounis and Neiman 2013).

Get Evonomics in your inbox

A rising share of capital income in total income implies that capital and capitalists are becoming more important than labor and workers—and thus acquiring more economic and political power. This trend occurred in both classical and liberal meritocratic capitalism, but not in the social-democratic variety (Table 2.1). A rising share of capital in total income also affects interpersonal income distribution because typically, (1) people who draw a large share of income from capital are rich, and (2) capital income is concentrated in relatively few hands. These two factors result almost automatically in greater income inequality between individuals.

To see why both (1) and (2) are indispensable for the automatic translation of higher capital share into greater interpersonal inequality, make the following mental experiment: assume that the share of capital in net income goes up, but that every individual receives the same proportion of income from capital and labor as every other individual. A rising aggregate share of capital income will increase every individual income in the same proportion, and inequality will not change. (Measures of inequality are relative.) In other words, if we do not have a high positive correlation between being “capital-abundant” (that is, deriving a large percentage of one’s income from capital) and being rich, a rising aggregate share of capital does not lead to higher interpersonal inequality. Note that in this example there are still rich and poor people, but there is no correlation between the percentage of income that a person draws from capital and that person’s position in the overall income distribution.

Now, imagine a situation where poor people draw a higher proportion of their income from capital than rich people do. As before, let the overall share of capital in net income increase. But this time, the rising share of capital will reduce income inequality because it will increase proportionately more the incomes of the people at the low end of the income distribution.

But neither of these two mental exercises reflects what is happening in reality in capitalist societies: rather, there is a strong positive association between being capital-abundant and being rich. The richer a person is, the more likely they are to have a high share of their income coming from capital. This has been the case in all types of capitalism (see Table 2.1, rows 2 and 3). This particular characteristic—that capital-abundant people are also rich—may be taken as an immutable characteristic of capitalism, at least in the forms that we have experienced it so far.

The next feature to consider is the link between being well-off in terms of capital (that is, being capital-income- rich within the distribution of capital incomes) and being well-off in terms of earnings (that is, being labor-income- rich within the distribution of labor incomes). One might think that people who are capital-abundant rich are unlikely to be rich in terms of their labor income. But this is not the case at all. A simple example with two groups of people, the “poor” and the “rich,” makes this clear. The poor have overall low income, and most of their income comes from labor; the rich are the opposite. Consider situation 1: The poor have 4 units of income from labor and 1 unit of income from capital; the rich have 4 units of income from labor and 16 units from capital. Here the capital abundant are indeed rich, but the amount of their labor income is the same as that of the poor. Now consider situation 2: Everything stays the same as in situation 1 except that the labor income of the rich increases to 8 units. They are still capital abundant, since they receive a larger share of their total income from capital (16 out of 24 units = 2/3) than the poor do, but now they are also labor-rich (8 units versus only 4 for the poor).

Situation 2 is when the capital-abundant individuals are not only rich but also relatively well off in terms of labor income. Everything else being the same, situation 2 is more unequal than situation 1. This is indeed one of the important differences between, on the one hand, classical and social-democratic capitalisms, and on the other, liberal meritocratic capitalism (see Table 2.1, row 4). The perception and reality of classical capitalism was that capitalists (what I call here capital-abundant individuals) were all very rich but typically did not receive much income from labor; in the extreme case, they received no income from labor at all. It is no accident that Thorstein Veblen labeled them the “leisure class.” Correspondingly, laborers received no income from capital at all. Their income came entirely from labor. In this case there was a perfect division of society into capitalists and workers, with both sides receiving zero income from the other factor of production. (If we add landlords, who received 100 percent of their income from land, we have the tripartite classification of classes introduced by Adam Smith.) Inequality was high in such fragmented societies because capitalists tended to have lots of capital, and the return on capital was (often) high, but inequality was not compounded by these same individuals also having high labor incomes.

The situation is different in liberal meritocratic capitalism, as found in the United States today. People who are capital-rich now tend also to be labor-rich (or to put it in more contemporary terms, they tend to be individuals with high “human capital”). Whereas the people at the top of the income distribution under classical capitalism were financiers, rentiers, and owners of large industrial holdings (who are not hired by anyone and hence have no labor income), today a significant percentage of the people at the top are highly paid managers, web designers, physicians, investment bankers, and other elite professionals. These people are wage workers who need to work in order to draw their large salaries. But these same people, whether through inheritance or because they have saved enough money through their working lives, also possess large financial assets and draw a significant amount of income from them.

The rising share of labor income in the top 1 percent (or even more select groups, like the top 0.1 percent) has been well documented by Thomas Piketty, in Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014), and other authors. What is important to realize here is that the presence of high labor income at the top of the income distribution, if associated with high capital income received by the same individuals, deepens inequality. This is a peculiarity of liberal meritocratic capitalism, something that has never before been seen to this extent.

16 November 2019

Excerpted from CAPITALISM, ALONE: THE FUTURE OF THE SYSTEM THAT RULES THE WORLD by Branko Milanovic, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!