July 8, 2024

By the mid 19th century, it was proven that hand-washing could slash hospital death rates. But it was water off a duck’s back to mid-19th-century surgeons. This was partly because it remained unexplained — indeed unexplainable — within the prevailing paradigm in which disease reflected an imbalance in the body’s four humours.

I thought of this reflecting on Ben Bernanke’s recent review of the Bank of England’s economic forecasting. As I argued last August, the Bank could dramatically improve the governance of forecasting by using open forecasting tournaments. Yet, the idea wasn’t even considered.

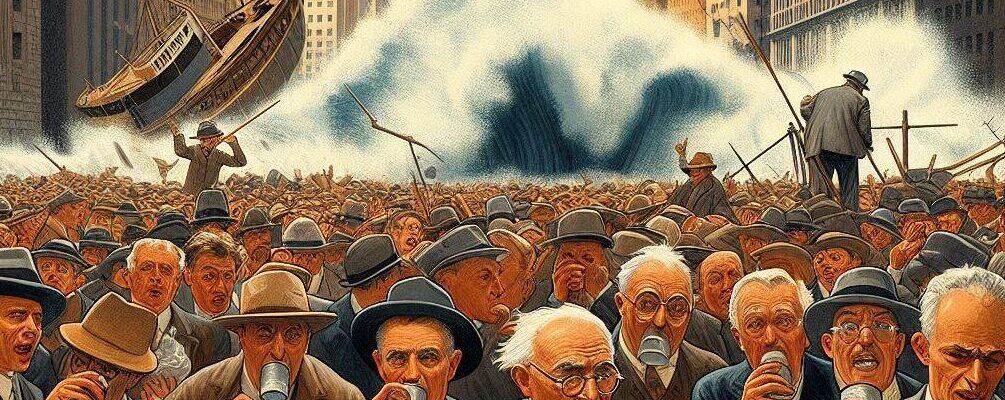

Economists are famed for their hubris, and their poor forecasting. In 1929, Prof. Irving Fisher famously forecast “a permanently high plateau” on Wall St. The Great Crash began within the week!

Following similar disasters after the 1973 oil price hike, the ‘Lucas critique’ shaped a new approach. Economists’ models had misforecast the economy because they were naïvely trained on data from a period when things were different — in this case when oil prices were far stabler.

Lucas’s answer was models that captured the structure of the economy. However, those models provide just one interpretation of economic structure and a radically simplified one at that. Their similarly dismal forecasting performance should have surprised no-one. But they surprised Lucas, who began by overestimating how much the problem could be tamed with updates to the economist’s technical toolbox and, like Fisher before him, then became wildly overconfident about the value of the result.

Good judgment is fundamental. Bernanke’s review discusses it, but its governance is a black box. Good judgement emerges from the back-and-forth between sound chaps within the Bank’s hallowed halls — he hopes.

So how do you find people with consistently good judgement and promote their status over the time-servers and the merely clever? As I know from chairing the data prediction platform Kaggle, neither their seniority nor their CV help. Though Dr Bernanke is probably an exception, you certainly don’t expect unusually good judgment from Nobel laureates in economics. Despite recent improvements, Nobels have mostly been awarded for cleverness, not usefulness. This was particularly so in the years during which Robert Lucas got his. There were quite a few others peddling similar wares.

Since the 1980s, psychologist Philip Tetlock has pioneered forecasting tournaments in numerous disciplines. Even to get them going, he had to pin forecasters down. Rather than tell us that some war, coup, or recession was “very likely,” he required them to nail down their percentage chances of being right, as weather forecasters do when telling us the chances of rain.

This gives us a far better evidence for sorting the also-rans from the ‘superforecasters’ who consistently outperform — like the superforecasters outperforming established economic forecasters right now in predicting the Fed’s funds rate.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

So what distinguishes superforecasters? They master purely cognitive, technical tasks where necessary, but they are also generously endowed with broader, more ethical and social epistemic virtues. They tend to be cautious, humble, self-critical, actively curious and open to alternative views. These qualities are neither taught nor assessed in university courses in economics — or other subjects, for that matter.

However, forecasting tournaments can teach these qualities (as they generate better forecasts) because they relentlessly reward whatever forecasters do to make themselves more accurate and less overconfident. They provide excellent institutional infrastructure for managing forecasting. They generate information about who is performing well and the incentives to match them, enabling experimentation with new approaches, including building teams with diverse skills.

All this has been kind of obvious for decades. Had we already embraced it, we would have moved on to new problems. Today’s four-day weather forecasts are as accurate as one-day forecasts 30 years ago. Yet improvements have gone missing in economic forecasting. That’s partly because it’s more difficult. (Human beings, unlike air molecules, worry and scheme. They cycle through collective gloom and euphoria.) But we won’t know till we take away the excuses. And even if forecasting tournaments don’t improve forecasting accuracy, they’ll improve forecasting.

First, by properly measuring and identifying outperformers, the focus turns to what works to improve forecasts, not going through the motions and keeping your nose clean with the higher-ups. Second, continually testing forecasts and forecasters’ confidence in those forecasts against unfolding events would expose and punish hubris. Third, a focus on changing confidence in forecasts should also help us detect turning points and provide better forward visibility for rare but highly consequential events like recessions and crashes. They matter more for economic decision-making than whether growth next year will be 1.75 or 2 per cent.

But with rare and unlikely events, how can we trust even superforecasters until they’ve built a track record over numerous cycles? Tetlock and his colleagues are onto it, exploring how forecasters narrow differences between themselves by persuasion and the extent to which superforecasting in one area should give us confidence in others.

I, for one, am relieved that superforecasting teams — no doubt viewing it from many angles — think an AI apocalypse is way less likely than AI pundits do.

Nicholas Gruen is CEO of Lateral Economics, Visiting Professor at King’s College London’s Policy Institute and inaugural Chair of Kaggle, a data prediction platform sold to Google in 2017.

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!