During the post war Golden Age, from 1950 to 1973, US median real wages more than doubled. Today, they are lower than they were when Jimmy Carter was President. If you want an explanation why Americans are pessimistic about their future, that is as good a reason as any. In a recent article, Noah Smith examines the various causes of the slide in labor’s share of national income and finds most explanations wanting. With a blind spot common amongst economists he doesn’t even investigate the most obvious: politics.

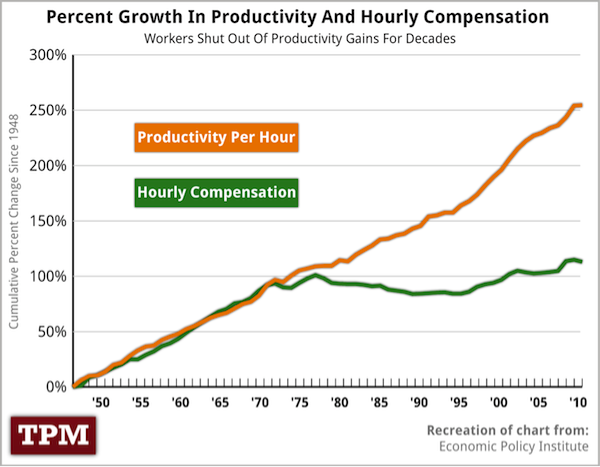

Take a look at this chart. From the end of World War II, productivity rose steadily. Until the 1972 recession wages went up alongside it. Both dipped, both recovered and then, right around the time Ronald Reagan became President, productivity continued its upward trajectory but wages stopped following. If wages had continued to track productivity increases, the average American would earn twice as much as he does today and America would undoubtedly be a calmer and happier nation.

Collectively we are richer than we were 40 years ago, as we should be, considering the incredible advances in technology since them, but today the benefits of productivity increases no longer go to workers but rather to owners of stocks, bonds, and real estate. Wages don’t go up, but asset prices do. Rising productivity, that is to say the ability to make more goods and services with fewer inputs of labor and capital should make us all more prosperous. That it hasn’t can only be a distributional issue.

The timing suggests Ronald Reagan had something to do stagnating wages. That makes sense. Reagan cut taxes on the rich, deregulated the economy, eviscerated the labor unions and created the neoliberal order that still rules today. But perhaps an even more significant change is the tiny, technical and tedious shift from fiscal to monetary policy.

Government has two ways of affecting the economy: monetary and fiscal policy. The first involves the setting of interest rates, the other government tax and spending policy. Both fiscal and monetary policy work by putting money in people’s pockets so they will spend and thereby stimulate the economy but fiscal focuses on workers while monetary mostly benefits the already rich. Since Ronald Reagan, even under Democratic presidents, monetary has been the policy of choice. No wonder wages stopped going up but real estate, stock and bond prices have gone through the roof. During the Golden Age we shared the benefits of technological progress through wages gains. Since Reagan, we have allocated them through asset price inflation.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

Fiscal policy, by increasing government spending, creates jobs and so raises wages even in the private sector. Monetary policy works mostly through the wealth effect. Lower interest rates almost automatically raise the value of stocks, bonds, and other real assets. Fiscal policy makes workers richer, monetary policy makes rich people richer. This, I suspect, explains better than anything else why monetary policy, even extreme monetary policy remains more respectable than even conventional monetary policy.

During the Golden Age, fiscal was king. Wages rose steadily and everybody was richer than their parents. Recessions were short and shallow. Economic policy makers’ primary task was insuring full unemployment. Anytime unemployment rose over a certain level, a government spending boost or tax cut would get the economy going again. And since firms were confident the government would never allow a steep downturn, they were ready and willing to invest in new technology and increased productive capacity. The economy grew faster (and more equitably) than it ever has before or since.

During the 1960s, Keynesian economists thought they could “fine tune” the economy, using Philips curve trade offs between inflation and unemployment. Stagflation in the 1970s shattered that optimism. Inflation went up but so did unemployment. New Classical economists decided in the long run, Keynesian stimulus couldn’t increase GDP, it could only accelerate inflation. Keynesianism stopped being cool. According to Robert Lucas, graduate students, would “snicker” whenever Keynesian concepts were mentioned.

In policy circles, Keynesians were replaced by monetarists, acolytes of Milton “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” Friedman. Volcker in America and Thatcher in Britain decided the only way to stomp out inflationary expectations was to cut the money supply. This, despite their best efforts, they were unable to do. Controlling the money supply proved almost impossible but monetarism gave Volcker and Thatcher the cover to manufacture the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

By raising interest rates until the economy screamed Volcker and Thatcher crushed investment and allowed unemployment to rise to levels unthinkable just a few years before. Businessmen, union leaders, and politicians pleaded for a rate cut but the central bankers were implacable. Ending inflationary expectations was worth the cost, they insisted. Volcker and Thatcher succeed in crushing inflation, not by cutting the money supply, but rather with an old fashioned Phillips curve trade off. Workers who fear for their jobs don’t ask for cost of living increases. Inflation was history.

The Federal Funds Rate hit 20% in 1980. Now even after a few hikes, it is barely over 1%. The story of the past 30 years is of the most stimulative monetary policy in history. Anytime the economy stumbled, interest rate cuts were the automatic response. Other than military Keynesianism and tax cuts, fiscal policy was relegated to the ash heap of history. Reagan of course combined tax cuts with increased military spending but traditional peacetime infrastructure stimulus was tainted by the 1970s stagflation and for policymakers remained beyond the pale.

Fiscal stimulus came back, momentarily, at the peak of the financial crisis. China’s investment binge combined with Obama’s stimulus package probably stopped the Great Recession from being as catastrophic as the Great Depression but by 2010, fiscal stimulus was replaced by its opposite, austerity. According to elementary macroeconomics, when the private sector is cutting back its spending, as it was still doing in the wake of the financial crisis, government should increase its spending to take up the slack. But Obama in America, Cameron in Britain and Merkel in the EU insisted that government cut spending, even as the private sector continued to retrench.

It is rather shocking, for anyone who has taken Econ 101 that in 2010, when the global economy had barely recovered from the worst recession since the Great Depression, politicians and pundits were calling for lower deficits, higher taxes and less government spending even as monetary policy was maxed out. Rates were already close to zero so central banks had no more room to cut.

So, instead of going to the tool box and taking out their tried and tested fiscal kit, which would have created jobs and had the added benefit of improving infrastructure, policymakers instead invented Quantitative Easing, which in essence is monetary policy on steroids. Central Banks promised to buy bonds from the private sector, increasing their price, thereby shoveling money towards bond owners. The idea was that by buying safe assets they would push the private sector to buy riskier assets and by increasing bank reserves they would stimulate lending but the consequence of all the Quantitative Easings is that all of the benefits of growth since the financial crisis have gone to the top 5% and most of that to the top 0.1%.

A feature or a bug? The men who rule the planet are happy that most of us think economics is boring, that we would much rather read about R Kelly’s sexual predilections than about the difference between fiscal and monetary policy but were we to remember that spending money on infrastructure or health care or education would create jobs, raise wages, and create demand which the economy craves, we would have a much more equitable world.

One cogent objection to stimulative fiscal policy is that it has the potential to be inflationary. Indeed the fundamental goal of macroeconomic policy is to match the economy’s demand to its ability to supply. If fiscal policy gets out of hand (as arguably it did in the 1960s when Lyndon Johnson tried to fund both his Great Society and the Vietnam war without raising taxes), demand could outstrip supply, creating inflation. But should that happen, we have the monetary tools to cure any inflationary pressure. Rates today are still barely above zero. Should inflation threaten, central banks can raise interest rates and nip it in the bud.

Fiscal and monetary policy both have a place in policymakers’ toolkits. Perhaps the ideal combination would be to use fiscal to stimulate the economy and monetary to cool it down. Both Brexit and Trump should have told elites that unless they share the benefits of growth, a populist onslaught could threaten all our prosperity. The easiest way to return to Golden Age tranquility and equality is to empower fiscal policy to invest in our future and create jobs today.

2017 August 6

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!