Anyone who has studied economics will be familiar with the ‘factors of production’. The best known ‘are ‘capital’ (machinery, tools, computers) and ‘labour’ (physical effort, knowledge, skills). The standard neo-classical production function is a combination of these two, with capital typically substituting for labour as firms maximize their productivity via technological innovation. The theory of marginal productivity argues that under certain assumptions, including perfect competition, market equilibrium will be attained when the marginal cost of an additional unit of capital or labour is equal to its marginal revenue. The theory has been the subject of considerable controversy, with long debates on what is really meant by capital, the role of interest rates and whether it is neatly substitutable with labour.

But there has always been a third ‘factor’: Land. Neglected, obfuscated but never quite completely forgotten, the story of Land’s marginalization from mainstream economic theory is little known. But it has important implications. Putting it back in to economics, we argue in a new book, ‘Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing’, could help us better understand many of today’s most pressing social and economic problems, including excessive property prices, rising wealth inequality and stagnant productivity. Land was initially a key part of classical economic theory, so why did it get pushed aside?

Classical economics, land and economic rent

The classical political economists – David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith – that shaped the birth of modern economics, emphasized that land had unique qualities, distinct from capital and labour, that had important influence on the dynamics of production.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

They recognized that land was inherently fixed and scarce. Ricardo’s concept of ‘economic rent’ referred to the gains accruing to landholders from their exclusive ownership of a scarce resource: desirable agricultural land. Ricardo argued that the landowner was not free to choose the economic rent he or she could charge. Rather, it was determined by the cost to the labourer of farming the next most desirable but un-owned plot. Rent was thus driven by the marginal productivity of land, not labour as the population theorist Thomas Malthus had argued. On the flipside, as Adam Smith (1776: 162) noted, neither did land rents reflect the efforts of the land-owner:

“The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.”

The classical economists feared that land-owners would increasingly monopolise the proceeds of growth as nations developed and desirably locational land became relatively more scarce. Eventually, as rents rose, the proportion of profits available for capital investment and wages would become so small as to lead to economic stagnation, inequality and rising unemployment. In other words, economic rent could crowd out productive investment.

Marxist and socialist thinkers proposed to deal with the problem of rent by nationalizing and socializing land: in other words destroying the institution of private property. But the classical economists had a strong attachment to the latter, seeing it as a bulwark of liberal democracy and encouraging of economic progress. They instead proposed to tax it. Indeed, they argued that the majority of taxation of the nation should come from increases in land values that would naturally occur in a developing economy. Mill (1884: 629-630) saw taxation of land as a natural extension of private property:

“In such a case …[land rent]… it would be no violation of the principles on which private property is grounded, if the state should appropriate this increase of wealth, or part of it, as it arises. This would not properly be taking anything from anybody; it would merely be applying an accession of wealth, created by circumstances, to the benefit of society, instead of allowing it to become an unearned appendage to the riches of a particular class.”

Ricardo and Smith were mainly writing about an agrarian economy. But the law of rent applies equally in developed urban areas as the famous Land Value Tax campaigner Henry George argued in his best-selling text ‘Progress and Poverty’. Once all the un-owned land is occupied, economic rent then becomes determined by locational value. Thus the rise of communications technology and globalisation has not meant ‘the end of distance’ as some predicted. Instead, it has driven the economic pre-eminence of a few cities that are best connected to the global economy and offer the best amenities for the knowledge workers and entrepreneurs of the digital economy. The scarcity of these locations has fed a long boom in the value of land in those cities.

Neoclassical economics and the obfuscation of land

The classical economists were ‘political’ in the sense that they saw a key role for the state and in particular taxation in preventing the institution of private property from constraining economic development via rent. But at the turn of the nineteenth century, a group of economists began to develop a new kind of economics, based upon universal scientific laws of supply and demand and free of normative judgements concerning power and state intervention. Land’s uniqueness as an input to production was lost along the way.

John Bates Clark was one of the leading American economists of the time and recognised as the founder of neoclassical capital theory. He argued that Ricardo’s law of rent generated from the marginal productivity of land applied equally to capital and labour. It mattered little what the intrinsic properties of the factors of production were and it was better to consider them ‘…as business men conceive of it, abstractly, as a sum or fund of value in productive uses… the earnings of these funds constitute in each case a differential gain like the product of land.’ (Bates Clark 1891: 144-145)

Clark developed the notion of an all-encompassing ‘fund’ of ‘pure capital’ that is homogeneous across land, labour and capital goods. From this rather fuzzy concept, developed marginal productivity theory. Land still exists in the short-run in this approach – and indeed in microeconomics textbooks – when it is generally assumed that some factors may be fixed. For example, you cannot immediately build a new factory or develop a new product to respond to new demands or changes in technology. But in the long run – which is what counts when thinking about equilibrium – all factors of production will be subject to the same variable marginal returns. All factors can be reduced to equivalent physical quantities – if a firm adds an additional unit of labour, capital good or land to its production process, it will be homogeneous to all previous units.

Early 20th Century English and American economists adopted and developed Clark’s theory in to a comprehensive theory of distribution of income and economic growth that eventually usurped political economy approaches. Clark’s work became the basis for the seminal neoclassical ‘two-factor’ growth models of the 1930s developed by Roy Harrod and Bob Solow. Land –defined as locational space – is absent from such macroeconomic models.

The reasons for this may well be political. Mason Gaffney, an American land economist and scholar of Henry George, has argued that Bates Clark and his followers received substantial financial support from corporate and landed interests who were determined to prevent George’s theories gaining credibility out of concerns that their wealth would be wittled away via a land tax. In contrast, theories of land rent and taxation never found an academic home. In addition, George, primarily a campaigner and journalist, never managed to forge an allegiance with American socialists who were more focused on taxing the profits of the captains of industry and the financial sector.

The result was the burden of taxation came to fall upon capital (corporation tax) and labour (income tax) rather than land. A final factor preventing theories of land rent taking off the U.S. may have been the simple fact that at the beginning of the 20th century, land scarcity and fixity was perhaps less a political issue in the still expanding U.S. than in Europe, were a land value tax came closer to being adopted.

Why land is different

At first glance, neoclassical economics’ conflation of land with a broad notion of capital does seem to follow a certain logic. It is clear that both can be thought of as commodities: both can be bought and sold in a mature capitalist market. A firm can have a portfolio of assets that includes land (or property) and shares in a company (the equivalent of owning capital ‘stock’) and swap one for another using established market prices. Both land and capital goods can also be seen as store of value (consider the phrase ‘safe as houses’) and to some extent a source of liquidity, particularly given innovations in finance that have allowed people to engage in home equity withdrawal.

In reality, however, land and capital are fundamentally distinctive phenomena. Land is permanent, cannot be produced or reproduced, cannot be ‘used up’ and does not depreciate. None of these features apply to capital. Capital goods are produced by humans, depreciate over time due to physical wear and tear and innovations in technology (think of computers or mobile phones) and they can be replicated. In any set of national accounts, you will find a sizeable negative number detailing physical capital stock ‘depreciation’: net not gross capital investment is the preferred variable used in calculating a nations’s output. When it comes to land, net and gross values are equal.

The argument made by Bates Clark and his followers was that by removing the complexities of dynamics, the true or pure functioning of the economy will be more clearly revealed. As a result, microeconomic theory generally deals with relations of coexistence or ‘comparative statics’ (how are labour and capital combined in a single point in time to create outputs) rather than dynamic relations. This has led to a neglect of the continued creation and destruction of capital and the continued existence and non-depreciation of land.

Indeed, although land values change with – or some would say drive – economic and financial cycles, in the long run land value usually appreciates rather than depreciates like capital. This is inevitable when you think about it – as the population grows, the economy develops and the capital stock increases, land remains fixed. The result is that land values (ground rents) must rise, unless there is some countervailing non-market intervention.

Indeed, there is good argument that as economies mature, the demand for land relative to other consumer goods increases. Land is a ‘positional good’, the desire for which is related to one’s position in society vis a vis others and thus not subject to diminishing marginal returns like other factors. As technological developments drive down the costs of other goods, so competition over the most prized locational space rises and eats up a greater and greater share of people’s income as Adair Turner has recently argued. A recent study of 14 advanced economies found that 81% of house price increases between 1950 and 2012 can be explained by rising land prices with the remainder attributable to increases in construction costs

Consequences of the neglect of land

Today’s economics textbooks – in particular microeconomics – slavishly follow the tenets of marginal productivity theory. ‘Income’ is understood narrowly as a reward for one’s contribution to production whilst wealth is understood as ‘savings’ due to one’s productive investment effort, not as unearned windfalls from being the owner of land or other naturally scarce sources of value. In many advanced economies land values – and capital gains made from increasing property prices – are not properly measured and tracked over time. As Steve Roth has noted for Evonomics, the U.S.’ National accounts does not properly take in to account capital gains and changes in household’s ‘net worth’, much of which is driven by changes in land values.

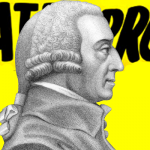

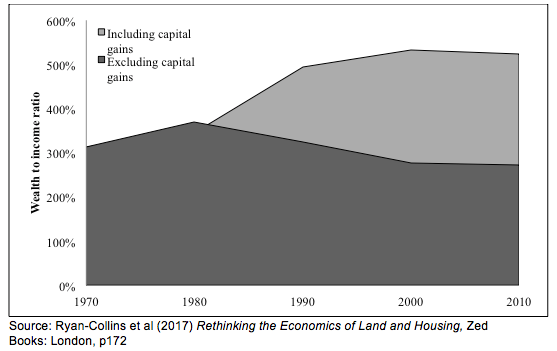

Even progressive economists such as Thomas Piketty have fallen in to this trap. Once you strip out capital gains (mainly on housing), Piketty’s spectacular rise in the wealth-to-income ratio recorded in advanced economics in the last 30 years starts to look very ordinary (Figure 1 shows the comparison for great Britain since 1970).

Figure 1: Piketty’s Wealth to income ratio including and excluding capital gains (Great Britain, 1970-2010)

Source: Ryan-Collins et al (2017) Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing, Zed Books: London, p172

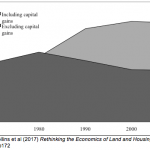

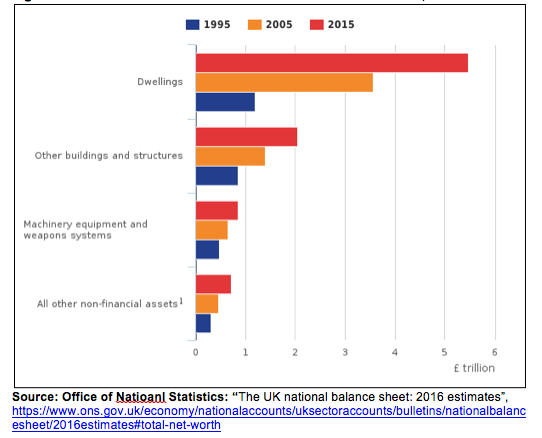

In the UK, land is not included as a distinct asset class in the National Accounts, despite being one of the largest and most important asset classes in the economy. Instead, the value of the underlying land is included in the value of dwellings and other buildings and structures, which are classed as ‘produced non-financial assets’ (Figure 2)

As shown in Figure 2, the value of ‘dwellings’ (homes and the land underneath them) has increased by four times (or 400%) between 1995 and 2015, from £1.2 trillion to £5.5 trillion, largely due to increases in house prices rather than a change in the volume of dwellings. In contrast the forms of ‘capital’ that we associate with increases in wealth and productivity – commercial buildings, machinery, transport, Information and communications technology has grown much more slowly.

Figure 2: Growth in the value of non-financial assets in the UK, 1995-2015

Thus this huge growth in wealth relative to the rest of the economy originates not from the saving of income derived from people’s contribution to production (activity that would have created jobs and raised incomes), but rather from windfalls resulting from exclusive control of a scarce natural resource: land.

This may help us explain – at least in part – the great ‘productivity puzzle’– that is, why productivity (and related average incomes) been flat-lining, even as ‘wealth’ has been increasing. The puzzle is explained by the fact that the majority of the growth in wealth has come from capital gains rather than increased profits (or savings) derived from productive investment, Savings are at a fifty year low in the UK even as the wealth to income ratio hits record highs.

When the value of land under a house goes up, the total productive capacity of the economy is unchanged or diminished because nothing new has been produced: it merely constitutes an increase in the value of the asset. This may increase the wealth of the landowner and they may choose to spend more or drawn down some of that wealth via home equity withdrawal. But they equally many not. Moreover, the rise in the value of that asset has a corresponding cost: someone else in the economy will have to save more for a deposit or see their rents increase and as a result spend less (or, in the case of the firm, invest less).

In current national accounts, however, only the increase in wealth is recorded, whilst the present discounted value of the decreased flow of resources to the rest of the economy is ignored as Joe Stiglitz has pointed out. Rising land values suck purchasing power and demand out of the economy, as the benefits of growth are concentrated in property owners with a low marginal propensity to consume, which in turn reduces spending and investment. In addition, most new credit creation by the banking system now flows in to real estate rather than productive activity. This crowds out productive investment, both by the banking system itself and non-bank investors who see the potential for much higher returns on relatively tax free real estate investment.

Land values also fundamentally effect the impact of monetary policy, particularly in financially liberalized economies. If a central bank lowers interest rates to try and stimulate capital investment and consumption, it is likely to simultaneously drive up land prices and the economic rent attaching to them as more credit flows in to mortgages for domestic and commercial real estate. This has a naturally perverse effect on the capital investment and consumption effects that the lowering of interest rates was intended to achieve.

Get Evonomics in your inbox

But for mainstream economists and policy makers these connections between the value of land and the macroeconomy are ignored. Housing demand is assumed to be subject to the same rules that drive desire for any other commodity: its marginal productivity and utility. Rising house prices or rents (relative to incomes) – an urgent problem in countries such as the United Kingdom – can be attributed to insufficient supply of homes or land. As with other policy challenges, such as unemployment, the focus of is on the supply side. The distribution of land and property wealth across the population, its taxation and the role of the banking system in driving up prices through increases in mortgage debt are neglected. Planning rules and other easy targets such as immigration are then blamed for the loss of control people feel as a result of insecure housing rather than its true structural causes in the land economy.

Land rents: there is a ‘free lunch’

Although presented as an objective theory of distribution, in fact marginal productivity theory has a strong normative element. Ultimately it leads us to a world, where, so long as there is sufficient competition and free markets, all will receive their just deserts in relation to their true contribution to society. There will, in Milton Friedman’s famous terms, be ‘no such thing as a free lunch’.

But marginal productivity theory says nothing about the distribution of the ownership of factors of production – not least land. Landed-property is implicitly assumed to be the most efficient organisational form for enabling private exchange and free markets with little questioning of how property and tenure rights are distributed nor of the gains (rents) that possession of such rights grants to its holders. Ultimately, this limits what the theory can say about the distribution of income, particularly in a world where such economic rents are large. Land is the ‘mother of all monopolies’ as Winston Churchill once put it – and hence the most important one for economists to understand.

But if economists are to focus on land, they must get their hands dirty. They must start examining the role of institutions, including systems of land-ownership, property-rights, land taxation and mortgage credit that are historically determined by power and class relations. In fact it is these inherently political, social and cultural developments that determine the way in which economic rent is distributed and with it, macroeconomic dynamics more generally.

2017 April 4

Smith, Adam (1776) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

Mill, John Stuart (1884) Principles of Political Economy, D. Appleton

Bates Clark, John Bates. (1891) ‘Marshall’s Principles of Economics’. Political Science, Quarterly 6 (1): 126–51.

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!