By Lixing Sun

For a long time, it wasn’t easy to be a Seahawks fan. People would look at you sideways, as if asking, “Are you serious?” And one thing you could be guaranteed was disappointment—year after year. But that was the 1990s. Today, if you wear a Seahawks jersey, chances are that you will be greeted with a proud hooray—“Go Hawks!”—anywhere in the Pacific Northwest.

The Seahawks made consecutive trips to the Super Bowl in 2014 and 2015, winning one and nearly the other. A key to its recent surge lies in the leadership of the quarterback Russell Wilson, whose salary was $526,000 and $662,000, respectively, for the two years, far below the team average of about $2 million. What could a low salary do to Wilson as a team leader?

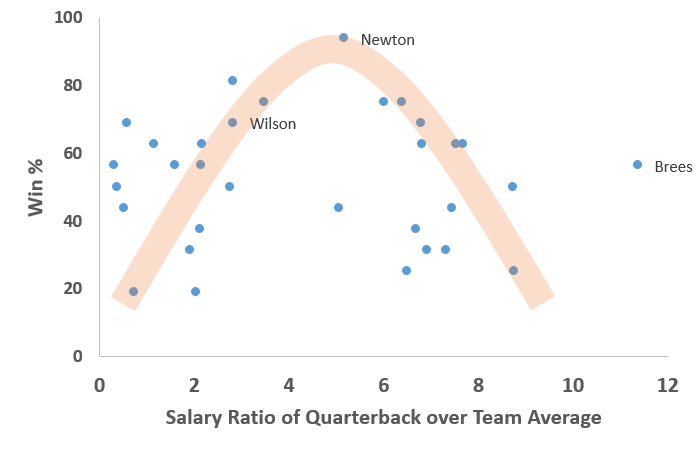

After some data crunching for the regular season of 2015, I found an NFL team that paid top dollar to its starting quarterback tended to do worse than that paid moderately less (see the chart drawn for the top 50 players for each of the 32 teams). No wonder the Saints have complained that Drew Brees is being paid too much ($23.8 million in 2015).

The chart shows an inverse-U relationship between performance and reward, also found in many similar psychological studies. Why could this be so?

Get Evonomics in your inbox

The answer lies in the fairness factor as I have elaborated in my book, The Fairness Instinct: The Robin Hood Mentality and Our Human Nature. For any organization, whether it’s a sports team or a business, if leaders take too much, they can jeopardize their credibility and demoralize those on the lower rungs. A larger difference in pay scale, as many studies show, will lead to a poorer performance for a pro basketball team or lower-quality products for a corporation. That’s why overpaying your quarterback will compromise your team performance.

If the Seahawks were lucky enough to pick up Wilson in the 3rd round (#75 overall pick) in 2012, the payoff for the franchise was redoubled when it paid the then unproven quarterback a dirt cheap salary—it helped Wilson quickly establish himself as the leader of the team.

Of course, Wilson isn’t the only talk of the town in Seattle. Dan Price, CEO of Gravity Payments, is another. Struck by an epiphany one day in early 2015, Price jumped out of his bed and announced to the world that he was to slash his own salary of $1.1 million by 90% and set $70,000 as the minimum wage for his company. He did so because he wanted people to be happy. And the $70,000 income, as studies show, brings the highest level of happiness. But the radical move stunned the nation and set off a firestorm in the media, drawing loud cheers as well as fierce denunciations.

Mr. Price may or may not know people see fairness very differently, from equality in opportunity to equality in outcome. Humans by nature are competitive, striving for relative advantage over their peers. For any organization, while extreme unfairness will incite internal strife, equal pay for all without merit will also kill the motivation to perform. So, there is a window where the fairness factor works the best. That’s what the inverse-U curve is all about.

Furthermore, low performers tend to prefer equality in outcome whereas high performers lean to equality for opportunities. By setting a high minimal wage and compressing the wage difference within his company, Price, while popular among low performers, reportedly faced the challenge of retaining high performers from financial lures from outside. Gravity, according to some nasty critics, would soon be nothing but a company of secretaries and janitors. Talk show host Rush Limbaugh trashed Price’s “experiment” as “socialism,” predicting, “it’s gonna fail.”

Obviously, these doomsayers forget that money is not the only incentive. Psychological and social wellbeing can also be potent rewards, which apparently have worked well for Gravity. A recent article in Inc., reports that Gravity’s profits have surged and the retention rate for the past three years has risen to 91%, well above the industry average of 68%. Moreover, Gravity has been flooded with applicants, including top talents like Tammi Kroll, a Yahoo executive, who would take a pay cut of 80-85% to work for Gravity.

Of course, it’s still too early to declare Price a winner in playing the fairness card. But as a Seahawks fan, I would be more worried about the Seahawks’ performance next season. Wilson’s salary was 2.83 times of the team average in 2015, but this ratio will shoot to 9 in the coming season. You can look at the chart to see why I am worried.

Illustration credit: Elliot Gerard. To see more artwork from Elliot, follow him on Instagram and Twitter @elliotgerard

2016 January 29

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!