By Lixing Sun

Socialism in America is perceived as a stigma that has dogged not only Sanders’s campaign but also Obama’s entire presidency. As a matter of fact, among all programs introduced by the Obama administration, nothing is more contentious than Obamacare, despite the fact that it cost less than 14% of Social Security’s $870 billion or about 20% of Medicare’s $597 billion in 2015.

Is socialism bad? From the sweeping success of many existing social programs (dealing with a wide range of concerns including retirement, healthcare, food, housing, energy, education, childcare, farming, and others), the answer, apparently, is no for most Americans. But why are new social programs unpopular today?

Get Evonomics in your inbox

A major, yet hidden, answer lies in social trust in America. New social programs such as Obamacare compete for tax revenue. Taxes are common-pool resources, and their use must be fair. If trust is low in a society, people will be inclined to suspect others’ motives and avoid being cheated by freeloaders. So, any social program paid with tax dollars won’t be popular. That’s how, for instance, a fictional story told by Ronald Reagan about a Chicago welfare queen could turn many Americans against the welfare system in the 1980s.

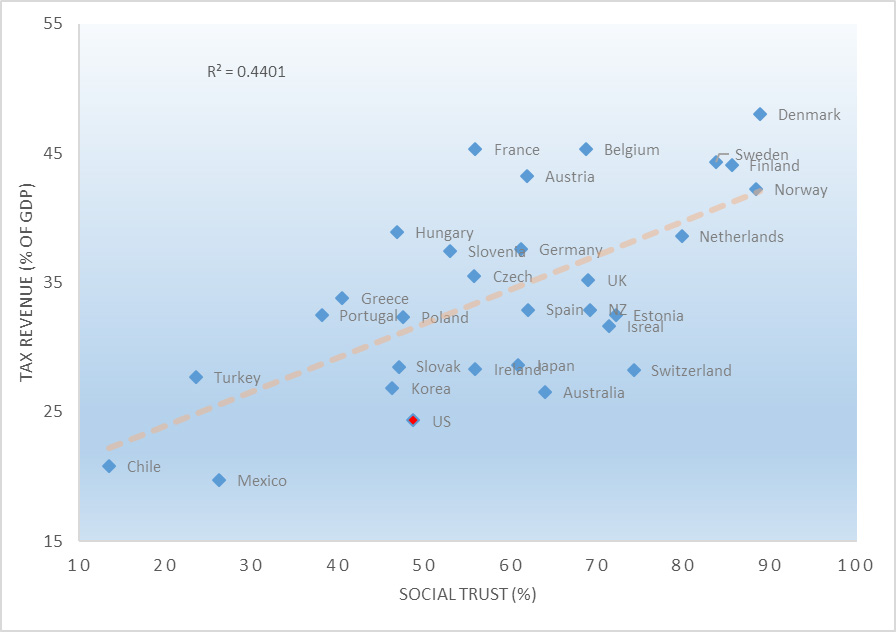

Existing data show that across the OECD nations, the higher the level of social trust, the greater the tax revenue. Statistically, trust accounts for a substantial portion (44%) of the increment in a nation’s tax revenue (see the chart below).

Apparently, to adopt a social democratic system like that in the Nordic counties, you need a trust level above 80%. With a trust level under 50% now, America simply doesn’t have the necessary social foundation for socialism. This explains much of why it posed such a challenge for Congress to get Obamacare passed and why Sanders has lost his presidential bid.

Although social trust is a non-material commons, it’s the psychological backbone of our society and the very foundation of desirable political, economic, and social exchanges. A breach of trust can trigger a barrage of societal problems. And its crippling aftermath can linger for years. Italy provides a great example, as shown by sociologist Robert Putman. Until recently, southern Italy, a low-trust area rife with clans, mafias, and gangsters, lagged behind northern Italy, a high-trust area free from these social ills, in social and economic development.

For economists, social trust works like a lubricant that can lower transaction costs and facilitate trading activities. Its aggregate benefit can be huge for a large economy, favoring the emergence and growth of large firms and boosting GDP with lower levels of inflation for a nation and higher levels of trade between nations. In America, according to Steve Knack, a World Bank senior economist, trust (broadly defined) was worth 12.4 trillion dollars a year, or 99.5% of the income in the mid-2000s. It “would explain basically all the difference between the per capita income of the United States and Somalia,” he remarked.

In a low-trust market, everybody has to pay more for transaction. Constantly guessing others’ intentions and looking out for cheaters, people are unwilling to invest in business and participate in financial markets, especially for the long term. (The Shanghai Composite Index, for example, could shoot up by 153% and then dive 43% in just 14 months from July 2014 to August 2015.) As a result, firms, as political economist Francis Fukuyama has observed, tend to be small, and mostly remain family businesses. This, in turn, can lead to lower rates of employment and higher rates of poverty.

Now, why is social trust so low in our society? Much of the drop in trust (by more than 10 points) since the late 1970s can be attributed to the polarization in wealth and decline in social mobility. Economic inequality, as so many studies have shown, can dissolve solidarity, tear social fabric, destabilize society, and foster revolts and revolutions. No wonder trust among people disappears as society becomes divided between haves and have-nots. When people don’t trust their governments and their fellow citizens, who would be excited to contribute to the financial commons—taxes? That’s why lower levels of trust lead to higher rates of tax evasion. This was how Greece, reputed for low trust in Europe, lost a third of its tax revenue in 2010 while the nation was trying to survive a sovereignty debt crisis.

Though America fares better in public finance, recent developments are disturbing as social trust slides. As neither the rich nor the poor are willing to pay more taxes, raising taxes has become such a hot-button issue that it takes a lot of guts for politicians to speak for it. As a result, many existing social programs are threatened and new ones are thwarted. The decline in social trust has begun to hurt us.

So, how can we boost social trust? Three main ways avail us.

First, ethnic and cultural uniformity. Similarity breeds trust. This may work for the Nordic countries dominated by Caucasian Christians but not for America, given our ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity.

Second, crises. The Great Depression spurred the birth of Social Security in the 1930s. World War II nurtured an unprecedented national solidarity, leading to the conception of the idea of Medicare during the Eisenhower administration. This was also a time marked by what economists Claudia Goldin and Robert Margo called “the Great Compression,” when the top tax bracket was 91% yet the economy still grew briskly. The Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassination of JFK, and the zeitgeist of building a “Great Society” ultimately helped LBJ to push through Medicare, together with many other social programs. Most recently, the 9/11 attacks by terrorists triggered a new surge in social trust among Americans, although the solidarity was short-lived due to an unpopular war and the persistence of economic inequality.

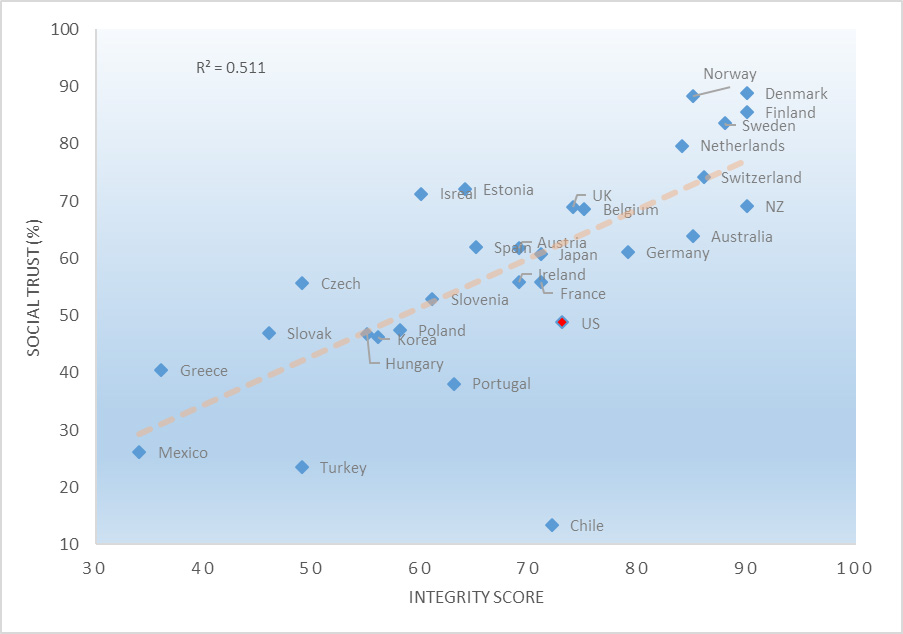

Finally, fighting government corruption and reducing economic inequality. Data from the OECD nations show that government integrity lifts (by as much as 51%) social trust (see the chart below). Therefore, a feasible way to promote social trust is to increase government responsibility, transparency, and accountability.

(Integrity score data from Transparency International*)

Why, you may ask, does the US score decently in government integrity but quite low in social trust? This is because America is relatively effective in fighting illegal hard corruption such as taking bribes or kickbacks (and thus has an acceptable score in government integrity). Our legal system, however, has little power in combatting soft corruption—corruption that is lawful but unethical—including patronage, investment, lobbying, and campaign financing. A common type of soft corruption is the practice of the “revolving door,” by which politicians get paid later for their favor done to special interests. It is the prevalence of soft corruption that has made many Americans resent political establishments, leading to the rise of such unlikely presidential candidates as Ben Carson and Donald Trump.

Fighting corruption can promote social trust and reduce the influence of lobbying from special interests. A rising level of trust will help progressive taxation, which can harness economic inequality, which in turn can promote trust. So fighting corruption, controlling economic inequality, and raising social trust can feed one another, leading to a much healthier democracy, stronger economy, and happier society, as the Nordic countries have shown us.

As our democracy becomes more and more tangled in money, fighting soft corruption is hugely popular. For instance, 85% of Americans desire an overhaul of the current campaign finance system. Obviously, our nation is overdue for a new Teddy Roosevelt who can reaffirm his vow that “we hold it to be prime duty of the people to free our government from the control of money.” Sanders would have gathered much more support had he run his campaign on fighting political corruption rather than on the stigmatized and misunderstood socialist platform.

2016 June 16

*: To avoid misunderstanding, I have changed “corruption score” used by Transparency International to “integrity score.”

Donating = Changing Economics. And Changing the World.

Evonomics is free, it’s a labor of love, and it's an expense. We spend hundreds of hours and lots of dollars each month creating, curating, and promoting content that drives the next evolution of economics. If you're like us — if you think there’s a key leverage point here for making the world a better place — please consider donating. We’ll use your donation to deliver even more game-changing content, and to spread the word about that content to influential thinkers far and wide.

MONTHLY DONATION

$3 / month

$7 / month

$10 / month

$25 / month

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

If you liked this article, you'll also like these other Evonomics articles...

Like Donald Trump, I Was Born on Third Base. But I Know Who Really Made me Rich.

The Basic Income and Job Guarantee are Complementary, not Opposing Policies

Why Countries Never Thrive Without Activist Government Investment

Before Capitalism, Medieval Peasants Got More Vacation Time Than You. Here's Why.

BE INVOLVED

We welcome you to take part in the next evolution of economics. Sign up now to be kept in the loop!